Tudor Dixon touts work at Michigan Steel. Foundry struggled to pay bills.

- Tudor Dixon has touted her work at family-owned Michigan Steel from 2002 to 2009

- The GOP gubernatorial hopeful left the company three years before it collapsed

- Records show the firm struggled to pay suppliers during Dixon’s tenure

MUSKEGON — An empty field marks the spot where Tudor Dixon began her professional career in Michigan’s steel industry, surrounding warehouses the only visible reminders of her family's foundry that shuttered in late 2012 and was later demolished.

Dixon, the Republican nominee for governor, has touted her seven years as an executive at Michigan Steel Inc. as evidence she’s prepared for “tough battles” as governor. She has distanced herself, though, from the eventual collapse of her father’s firm, which occurred three years after she left the company upon becoming pregnant with her first child.

But court records reviewed by Bridge Michigan indicate the Muskegon foundry struggled with cash flow while Dixon worked there, well before Michigan Steel laid off its entire workforce — which had topped at near 300 employees — and liquidated the company her dad purchased in 2002.

Related:

- Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has 28-1 cash edge over Tudor Dixon, reports show

- Dixon, Hernandez ticket prevails in contentious Michigan GOP convention

- Drag queens and MAGA: Tudor Dixon fights culture wars in Michigan governor bid

More than two dozen suppliers sued Michigan Steel during Dixon's tenure. The non-union company also generated several safety violation citations, worker injuries and emissions complaints from neighbors.

"They were always slow payment," said Tim Kmiecik. CEO of White Eagle Steel of Spring Lake, which sued Michigan Steel over unpaid bills from 2008.

"It seemed to be half-assed, to be quite frank."

Dixon's campaign declined an interview request about her tenure at the steel foundry. In an email, a spokesperson said Dixon was “not involved in or aware of any of the lawsuits” and described her role in the company in more limited terms than she has in the past.

Dixon primarily worked as a sales executive, where her objective was to “grow revenues,” which rose from $8 million annually to “over $30 million when she left in 2009," said the spokesperson, Kyle Olson.

By that time, the Great Recession had hit Michigan manufacturing hard. And supporters contend Dixon’s work in the male-dominated foundry showed she has the “grit” to lead the state despite having never held political office.

Dixon was raised in suburban Chicago, studied psychology at the University of Kentucky and then worked as a production assistant for the Oxygen Network television station.

She moved to Michigan in 2002, where her father, Vaughn Makary, hired her to work at the aging foundry he had bought out of bankruptcy. Her husband, Aaron Dixon, got a job there, too.

Markary, who died in June, had previously helped run a steel casting company in Illinois and served as president of the Steel Founders’ Society of America in 1996 and 1997, according to the Muskegon Chronicle.

Dixon worked in sales and later human resources but told Bridge Michigan earlier this summer she eventually helped run “every aspect” of the business.

“I was really helping him (her dad) make the big decisions, but went from dealing with the small things on the customer service side to everything that had to do with our largest deals with customers across the globe,” Dixon said earlier this summer.

She also promoted her leadership at the foundry following her victory in the Republican primary in August, citing the difficulty of “running and growing” the company as a woman.

According to Dixon's campaign, Dixon took over Human Resources during her final six months at Michigan Steel. By that point, the sales team, customer service team and HR reported to her, Olson said.

The Republican gubernatorial hopeful left Michigan Steel in 2009, exiting the company amid the Great Recession to start a family. That was three years before Michigan Steel collapsed amid tax liens, unpaid property taxes, layoffs and bounced checks to employees.

Dixon later returned to the steel industry briefly before founding a conservative news service for schools and co-hosting a show on Real America’s Voice, a right-wing news network that introduced her to national political figures and put her in the orbit of former President Donald Trump, who endorsed her in late July.

Unpaid bills

Dixon’s campaign said that after she left, she had "no involvement" in Michigan Steel in the final three-and-a-half years before the foundry closed. When she left in 2009, the company “just suffered the 2008 downturn, which negatively impacted the entire manufacturing industry,” said Olson, the campaign spokesperson.

Dixon, who is seeking to oust Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, has “hands-on experience” that helped her understand “how businesses actually work in the real world and how much big-government policies really stifle growth, prevent job creation and hold down wages for workers,” Olson said.

“When Gretchen Whitmer weaponizes government agencies against our businesses — or shuts them down and locks out their customers — it underscores her lack of real-world experience,” he added.

The global steel industry was growing when Dixon's father took over the Muskegon foundry in 2002, but Michigan Steel was not the only domestic foundry that struggled to stay in business over the next two decades.

There were 350 steel foundries in the U.S. in 2000 but just 150 still operating in 2020, according to Raymond Monroe, current executive Vice President of the Steel Founders’ Society of America.

He blamed globalization — more than the Great Recession — for struggles at foundries like Michigan Steel, which specialized in producing valves that customers were able to begin buying from China at lower prices.

Global competition was the "biggest factor" in Michigan Steel's demise, Monroe told Bridge. "They probably were just a casualty of the business environment with management that was not creative enough to survive."

Court records show Michigan Steel struggled to pay suppliers during Dixon’s tenure, which predated the Great Recession and was a period of generally healthy profits in the U.S. iron and steel industries.

The company, which sat on 1,700 feet of Muskegon Lake frontage in a heavily industrial area of the city, was sued by vendors more than two dozen times over unpaid bills from 2003 to 2009, the year Dixon left the company, including 10 lawsuits prior to 2007, according to court records.

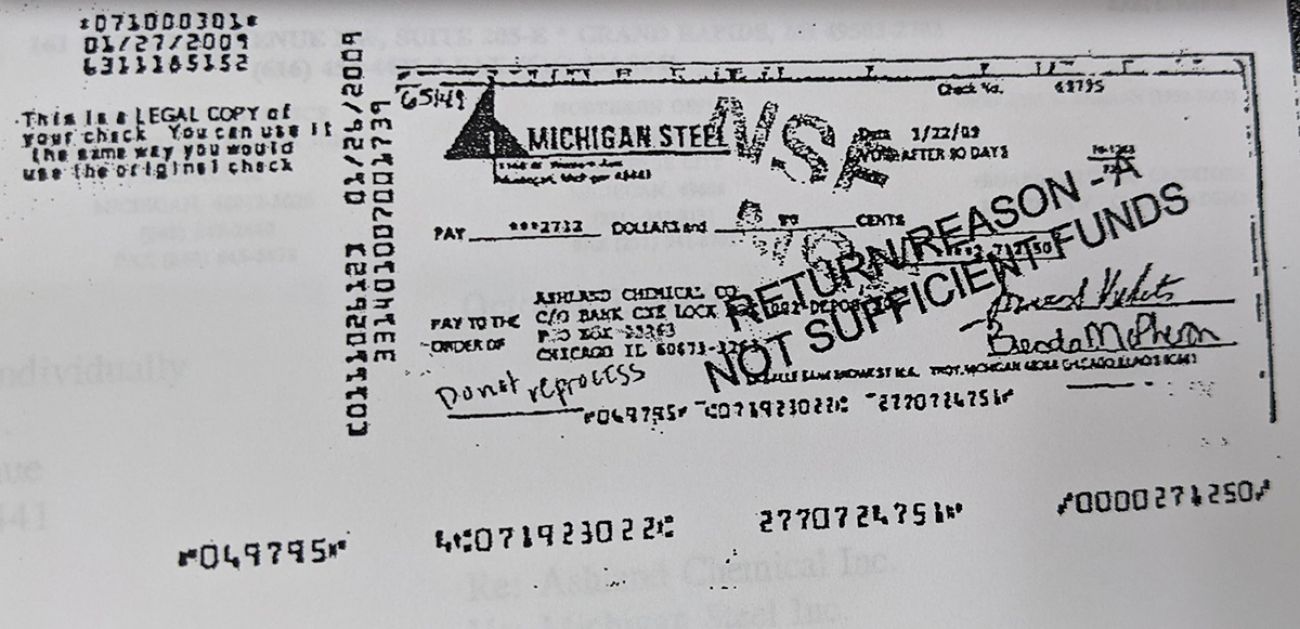

Among other things, plaintiffs allege the foundry did not pay trash and gas bills, bounced checks to suppliers and was forced to return rented forklifts.

In most cases, Michigan Steel settled with suppliers in court. But the firm was accused of failing to honor settlement terms in at least three cases, had property seized by court officers as early as 2008 and did not pay off all judgments before closing in late 2012 and liquidating early the next year.

In 2005, a boom year for the steel industry, Consumers Energy sued Michigan Steel over a $51,055 natural gas tab, alleging the company "failed and refused to pay" its bills in a "material breach of contract," according to court records. In a Jan. 31 email, an office manager told Consumers the company had been "unable to keep up" with payments because the fourth quarter of 2004 "was not as robust as we had predicted,” according to court documents.

White Eagle Steel sued over $30,775 in unpaid bills in 2009 dating back to the prior year. The firm was eventually paid through a court settlement, but the legal fight was emblematic of long-running issues at the foundry, said Kmiecik, the White Eagle CEO.

Michigan Steel appeared to be maintaining its own operation by using "other companies’ money," essentially borrowing funds by delaying payments, Kmiecik said. It’s not the only company in the steel industry that used that business model, but it was a "standout," he said.

"Thank God not everybody's like that," he told Bridge.

In 2009, Waste Management suspended trash service at Michigan Steel and sued the company for $62,074, demanding payment for unpaid bills and service charges from 2008. A default judgment authorized court officers to seize and sell Michigan Steel's personal property but the foundry went out of business before Waste Management was able to recoup its full losses.

Authorities had collected $20,000 from Michigan Steel by April 2013, when a court officer visited the foundry again but informed the court that "no property was seized" because the "business has closed and is no longer operational."

Court records show General Electric Capital, the parent company of Alta Lift Truck, sued Michigan Steel in 2010 for $313,402 in unpaid bills dating back to 2008, when Dixon said she was working alongside her dad in a leadership role. The foundry was eventually ordered to return 11 forklifts it had rented from the firm, but it’s not clear if Michigan Steel was able to pay off its full debt before going out of business in 2013.

Michigan Steel officials blamed economic factors that began with the Great Recession, which hit Michigan particularly hard and early in 2008 and 2009.

The economic downturn was "tough" on the steel industry, acknowledged Kmiecik, the CEO of White Eagle Steel in Spring Lake. "It's kinda like today's market: Prices just went out of sight. If you were big enough to order from the mills, you had to predict what you were going to use eight months in the future."

But as a 31-year steel industry veteran, Kmiecik said he's gotten to know "the good, bad or kind of in-between. And Michigan Steel, he said, "seemed to fall between the bad and in-between."

A ‘great place to work’

Despite the company’s eventual collapse, Michigan Steel had been a “really great place to work,” said Angela Himber, who was a sales administrative assistant and customer service representative at the company from 2005 to 2009.

Dixon was her supervisor in the sales department and was "very kind, generous," Himber told Bridge Michigan, saying she still considers Dixon a friend. "She always tried to be there for everybody that worked there."

As a salesperson, Dixon traveled across the country meeting with customers like John Deere and Caterpillar, Himber recalled.

She also joined her father on some larger-scale projects, including a trip to France where they secured mold patterns that allowed the company to start producing steel axles for military vehicles, Himber said.

But slow payments for those parts ironically helped doom Michigan Steel, according to Himber, who attributed the foundry's eventual demise to the resulting cash flow crunch coupled with ongoing effects of the earlier Great Recession.

"All of those things put together was like the perfect storm for this company," she said.

Dixon's campaign confirmed Michigan Steel supplied axle housings for Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles to a company that was headquartered in Wisconsin and had a facility in Lyon, France.

By September 2009, at the peak of the Great Recession, Michigan Steel had laid off 160 production and staff workers, about 61 percent of its total workforce, according to a letter the company sent to the state explaining a delayed response to an environmental citation.

Before she left the company that year, Himber recalled how she and other Michigan Steel workers watched the economy “crashing right before our eyes” and tried to "to ship parts as quickly as possible” before big customers began canceling orders.

Dixon, Himber and another female co-worker in the sales department had "stuck together" because it was a "male dominated industry." When there was "sexual harassment or anything like that, (Dixon) usually handled it and moved on," Himber recalled. "She didn't let it affect her."

Salespeople like Dixon were often in the foundry "watching big pours" of steel, or sorting parts if an order needed to be shipped as quickly as possible, Himber said. "It was all hands on deck. There were no limitations to what type of work we needed to do to get the parts to customers,” Himber said.

Himber, who said she still talks to Dixon when their paths cross, told Bridge she thinks the Norton Shores Republican would make an excellent governor.

Dixon has "grit" and is a "hard worker who will go the extra mile to get it done," Himber said. "She's a really good salesperson, and she has a really good sense of business. I definitely, truly believe that she is what Michigan needs."

Dixon was active in industry groups and chaired the Steel Founders’ Society of America's "future leaders committee,” said Monroe of the industry group.

"She was just absolutely a spectacular person to work with," Monroe recalled. "Bright, caring, capable. She was just a delight."

‘Extreme’ hardship

Three years after Dixon said she left Michigan Steel to start a family, the firm’s financial woes appeared to compound.

In late 2012, employees began to report bounced checks to the state as the foundry laid off most workers and closed prior to liquidation in early 2013.

Dozens of employees, including the company's CEO, filed wage complaints with the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs in 2012 and 2013, according to records obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. Names were redacted.

The CEO claimed he was owed $34,000, while another white collar worker had initially tried to recoup a $40,000 bonus he said he had been verbally promised. But most claims were much smaller. A “grinder/press operator” paid $12 per hour said he was stiffed $1,476. A production worker who made $10.21 an hour was owed $372, according to a complaint.

In layoff letters sent to employees, Michigan Steel said “economic conditions” made it “necessary to reduce our labor force.” And a human resources worker told the state the company was "under extreme economic and financial hardship.”

The state repeatedly fined Michigan Steel for violating Michigan wage laws. But after the foundry closed, the state sent letters to several workers explaining they would never be paid because Michigan Steel had "no available finances or assets to collect monies owed to you."

Michigan Steel had experienced "a significant cash shortage" in prior months and had "ceased normal business operations," attorney Robert Wardrop II wrote in an early 2013 letter to creditors that was shared with the state.

Foundry operators saw no point in going through bankruptcy because there would be “no benefit” to most creditors, Waldrop added. "In the end, it became clear that the company had to liquidate.”

The foundry melted about 877 tons of steel between June and August of that year, down from 2,642 tons over the same span in 2008, according to the letter, obtained under a Freedom of Information Act request.

Michigan Steel’s eventual collapse was tough for the Muskegon community, which had already been rocked by years of industrial-era business losses, said Brett Gilbert, owner of the nearby Fatty Lumpkins Sandwich Shack, which opened in 2011.

"I was born in 1981, so basically my entire life it's been industry leaving town, and that was sort of the last one, " he told Bridge. "It never helps us to lose large employers close by."

‘A really tough industry’

Dixon has touted the foundry’s sterling workplace safety record, arguing businesses know best as she promised to cut government regulations and attacked Whitmer over pandemic response orders the Democratic governor announced as an effort to protect public health.

"I come from the foundry business" and "we started every meeting with a safety meeting," Dixon said in a July interview with conservative activist group Stand Up Michigan.

"Every company knows to succeed, you have to keep your customers and your employees safe," Dixon added, arguing Whitmer has "weaponized" state regulators against businesses.

But public records and news reports indicate there were several workplace injuries in her family’s aging Michigan Steel foundry, which was also fined more than $28,000 for regulatory violations by the Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration between 2004 and 2008.

During that span, one Michigan Steel worker was reportedly hospitalized after getting his arm caught in a "core-making machine,” another was hospitalized after a furnace explosion led to burns on his hands, face and arms and a third employee suffered third-degree burns while moving molten metal, according to reports in the Muskegon Chronicle.

"Nobody wanted to work there because it was so friggin' dangerous." said a former human resources employee who asked not to be identified because the employee had signed a non-disclosure agreement as part of a severance package.

"I was informed that if someone walks in and wants a job, give it to them no matter what.”

Environmental inspection records show local residents occasionally complained of odors emanating from the Michigan Steel foundry, along with "fall down" as dust and other particulate matter rained down on their homes, cars or boats docked on Muskegon Lake. The state cited the firm for air quality violations on multiple occasions prior to 2009, when Dixon left.

In the foundry's final year of operation, one employee (whose name was redacted from state records) alleged dust control equipment failed nearly two years prior but was never replaced, creating emissions "so strong" the company put garden hoses and sprinklers on top of a large "baghouse" filter to tamp down the dust.

By the time state inspectors visited the facility, it was already in the process of closing, however, and they did not issue another air-quality violation.

“The industry was struggling” when Dixon’s father bought the foundry out of bankruptcy, said Dennis Kirksey, a Muskegon business and environmental leader who operated out of the building next door for three decades.

"The predecessor struggled, and they struggled," Kirksey said of Michigan Steel.

"It was busy, but I think part of their downfall was it was a really old factory," he told Bridge.

"There were just too many places in that plant for employees to hide. People could look busy just moving from one place to another and not really accomplishing anything."

The foundry was so old "there were portions where you would swear it was a dirt floor," Kirskey said, noting the sands that coated the floor were actually "shake out operations" from casting molds.

"It was dirty," he said. "It was nasty."

Still, Dixon's father was "respected within the manufacturing community," Kirskey told Bridge. He "had to make hard decisions on a daily basis, so I think among the manufacturers in the area, there was mutual respect."

Makary certainly "got into financial hardships in different spots, but it was kind of the nature of that industry," said Kirksey, a local developer who saw the foundry’s previous owners struggle too. "It was a really tough industry to make a buck in.”

Working next door, Kirskey said he also "came to know" Dixon and her husband, who also worked at the foundry. He didn't recall specific titles Dixon held but recalled she worked "more on the managerial side of the operation."

Kirskey, who described himself as a fiscal conservative, told Bridge he supports Dixon's bid to be the state's next governor, saying he thinks it is important for the state’s highest-ranking official to have "some real world experience, especially with the blue-collar workforce."

"I think her time in industry overall helps prepare her for the job," he said. "There's decisions you have to make in either position that I think come better from a business perspective than they do from just a poly-sci teaching."

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!