Michigan's newest PFAS threat: Contamination from household septic systems

- A state probe of private drinking-water wells in Cadillac reveals the dangers of PFAS in common household products, from laundry detergent to floor wax

- State officials say PFAS likely leached into the groundwater after residents unknowingly flushed tainted wastewater into their septic systems

- The incident has shaken Cadillac, while highlighting a risk to millions in Michigan who own private wells and septic systems

Cadillac residents had been on edge for months about the discovery of toxic “forever chemicals” in dozens of private drinking water wells, when state officials recently delivered some unexpected news.

The most logical culprit, many had believed, was a local industrial park with a troubled history. After all, metal platers and automotive manufacturers had already polluted the park with volatile organic compounds and hexavalent chromium. Those same industries have been linked to PFAS contamination in other Michigan communities. And Cadillac’s first PFAS-positive well test had come from a home within the industrial park.

But a state analysis of water from 70 neighboring wells told another story: Some residents, schools and businesses may have unwittingly tainted their own drinking water, through years of flushing common household products down the drain and into septic systems that allowed tainted sewage to quietly infiltrate the aquifer.

“We're really guessing at the sources at this point,” said Abigail Hendershott, executive director of the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team within the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy.

“But when you get this many of them, especially since there's no real industrial sources (within the immediate vicinity) … a lot of these are going to be small, diffuse sources such as septic fields.”

Related:

- Up to 3.2M in Michigan may be getting water from PFAS-tainted aquifers

- EPA seeks lower PFAS drinking water standard: What it means for Michigan

- 3M to stop making PFAS ‘forever chemical.’ Michigan asks what took so long?

- For Ann Arbor water managers, ongoing battle to keep toxic chemicals at bay

Cadillac’s experience serves as a warning to millions of Michiganders who drink from unmonitored, loosely regulated private wells and flush their household sewage into onsite septic systems: PFAS is pervasive in everyday products, from shaving cream and laundry detergent to floor wax and wrinkle-free clothes. And septic systems are not designed to break them down.

Addressing highly localized pollution caused by those products is “the next stage” in a nationwide contamination response that so far has focused mainly on major polluters like factories and military bases, said Cheryl Murphy, director of the Michigan State University Center for PFAS Research.

“It's a tricky place to be, when we're all contributing to it,” Murphy said. “In order to deal with this, we have to emphasize that yes, it's in your households, but there are steps that you can take to minimize your exposure.”

Namely, getting well water tested, installing filters if needed, and thinking twice about the chemicals we use in our homes.

The hunt for a culprit

Like dozens of communities dealing with PFAS contamination, Cadillac’s story began with a troubling discovery in a neighborhood known for pollution.

JT Anderson has lived for 17 years in the city’s industrial park — an area so sullied by industry that officials have spent decades cleaning toxic chemicals from the groundwater. Most neighbors were switched to city water long ago, but the former owners of Anderson’s home apparently declined.

With the dangers of PFAS in the national spotlight, in recent years some residents and federal environmental regulators had begun to raise concerns about potential PFAS contamination in the industrial park and demand the city take action. At a friend’s urging, Anderson got his own water tested.

“Me and my wife want to enjoy our grandkids,” he said. “We don’t want to be sick all the time.”

Known as “forever chemicals” because they can persist in the environment for centuries, PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of thousands of chemicals that have been linked to cancer, thyroid problems, developmental issues, hormone, fertility, and immunity challenges.

Valued by manufacturers for their strong chemical bonds that resist grease and water, they were used for decades with little regulation, leading to widespread pollution.

Anderson’s well water contained one compound, called PFOA, at 9 parts per trillion — just above state health criteria of 8 ppt.

He lives a block away from a former metal plater, the type of business known to use lots of PFAS. So in response, the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team added the park to a long list of suspected contaminated sites, and set about testing nearby wells to see if the pollution had spread.

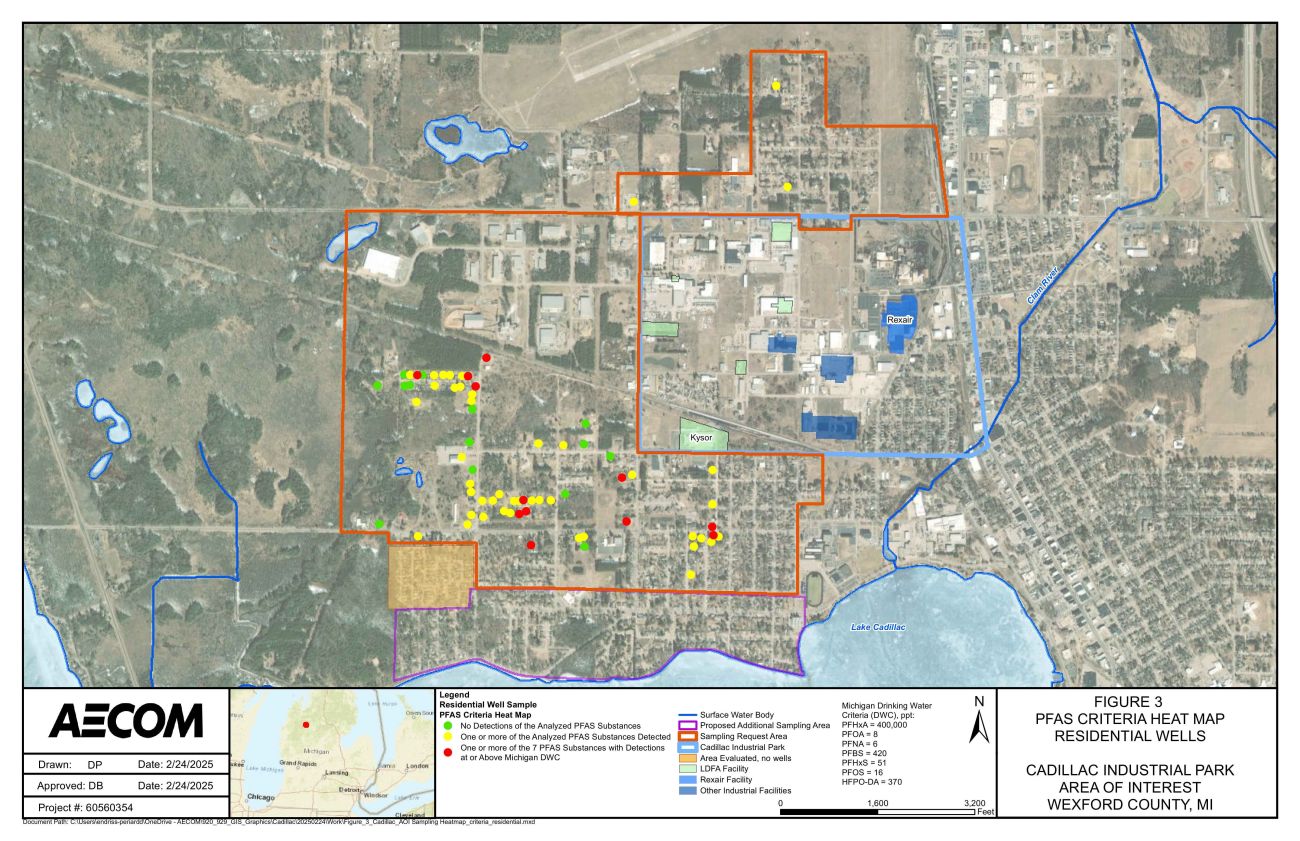

But while 56 out of 70 tests came back with at least a trace of PFAS, most of them lacked any clear link to the industrial park.

“We’re not seeing that smoking gun, so to speak,” said Hendershott.

Groundwater generally flows northward from the park, but many tainted wells were located to the south and west. On any given block, one well might be hot, while the next had little to no PFAS. And the types of PFAS varied from property to property — a sign that they were contaminated by different sources.

Meanwhile, PFAS has cropped up at new sites far from the original study area — a school property more than a mile to the east, and a car dealership and dentist’s office south of town.

Investigators now believe that with the exception of wells located directly in the industrial park, most were tainted not by heavy industry, but by a mix of smaller sources, such as septic systems that accumulated PFAS one floor-cleaning or laundry load at a time.

“It’s a terrible situation,” said City Manager Marcus Peccia. “And it’s a situation in which Cadillac is absolutely not unique.”

Few regulations

Despite growing evidence of the health risks associated with PFAS (something chemical companies knew long before the public), they’re still incorporated into a dizzying array of products. To name just a few: Toilet paper, nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpet, waterproof clothing, firefighting foams, cleaning solutions, asphalt sealants and tampons.

“These are a very large class of chemicals, and very few of them have been regulated for safety before they got out onto the market,” said Erica Bloom, toxics campaign director with the Ann Arbor-based Ecology Center.

Customers of public drinking water systems are at least partially protected from exposure, thanks to recently enacted state and federal regulations that require utilities to test for PFAS and remove it if found.

But some 2.6 million Michiganders drink from private wells that aren’t subject to testing and water quality standards. Many of the same households are also served by private septic systems, which dispose of sewage by trapping solids in a tank while the liquids gradually seep back into the aquifer.

It's a failure-prone system that has been blamed for polluting Michigan’s lakes and rivers with human waste. And even properly functioning septic systems weren’t designed to break down today’s synthetic chemicals, said Michael Jury, a PFAS specialist with EGLE.

“There's a lot of interesting chemicals — everything from antidepressants and other things — showing up in surface water and lakes,” Jury said. “A lot of those are coming from septic tanks.”

Cadillac’s municipal water has always tested PFAS free. But about 223 of the city’s 3,800 households remain on private wells. Of the 70 tested by the state, 12 contained PFAS at levels that would not be allowed in public drinking water. The highest reading was 340 ppt of a PFAS compound called PFHxS, which is more than six times the state standard.

The state is providing water filters to residents with contaminated wells, while the city seeks grants to cover the cost of hooking well-owners up to municipal water.

A search for answers

Many of the tainted wells are concentrated on Marathon Drive, a rare part of the city that isn’t serviced by water and sewer lines. Jim Stiver, who has lived there for 36 years, said some residents still flush laundry water into simple perforated drums buried underground.

“Who can you blame?” said Stiver, who recently learned his well water contains PFAS. “How many people buy a jug of detergent and turn it over to read what’s in it? They just wash their clothes.”

Some local water activists have expressed skepticism that septics are to blame, arguing city officials haven’t fully investigated other possible causes of contamination. They’ve launched their own effort to collect data about where else PFAS may have spread, and how.

“We are holding EGLE accountable, we are holding the city of Cadillac accountable to continue to find the sources,” said Mary Galvanek, co-founder of the group Cadillac Advocates for Clean Water. “We are not going to just say, ‘Oh, it’s probably septic tanks,’ and then walk off.”

The controversy has spiraled into a tense debate about whether city officials should have uncovered the PFAS problem earlier. There have been resignations on the city council, calls for investigations about who knew what and when, and even death threats against public officials.

Peccia, whose family was a target of those threats, called the whole situation “unfortunate.”

“The city did not put the contaminants in the ground,” Peccia said. “We didn’t cover anything up. We didn’t poison anybody. And I’m not suggesting that anybody maliciously did it to themselves either. We just didn’t know.”

State officials acknowledge that some wells could have been contaminated in other ways. For example, a car fire that was extinguished with PFAS-containing firefighting foam. But data from throughout the country underscores why household waste is a prime suspect.

In New Hampshire, PFAS consistently turned up in tests of septic tank sludge. In Wisconsin, tests of shallow private wells across the state revealed widespread PFAS mingling with artificial sweeteners, pharmaceuticals and other substances found in human waste — a telltale sign that the pollution came from septic systems. A study in New York produced similar findings.

“If there’s septic system discharge, (PFAS) is in the waste stream,” said Bill Phelps, a hydrogeologist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources who coauthored the Wisconsin study.

“The real message is for people on private wells to realize that it’s not unlikely those chemicals might be in their water.”

“The real message is for people on private wells to realize that it’s not unlikely those chemicals might be in their water.” — Bill Phelps, hydrogeologist.

Michiganders who get their water from private wells should get it tested if they can afford it, Bloom said. Testing through a certified lab costs about $300, although cheaper uncertified tests such as Cyclopure can be a useful screening tool.

“Even beyond PFAS,” Bloom said, “it's not a bad idea to know what's coming out of your tap.”

Tackling the supply chain

The key to avoiding contamination from household waste, Murphy said, is to be more careful about the cleaning chemicals, clothing and other goods we bring into our homes.

“It’s being aware of what products actually have PFAS in them, and then starting to lower your use,” she said.

That advice applies to septic system owners and city sewer customers alike: Municipal sewage treatment plants also weren’t designed to remove PFAS, which means the chemicals escape into the wastewater that’s piped into area waterways, and sewage sludge that’s applied to farm fields.

“We have to stop putting it into the environment, so that it stops building up,” Murphy said.

US chemical safety laws don't make it easy.

Federal law doesn’t require manufacturers to warn the public if their products contain PFAS. Some states have enacted PFAS labeling laws, but similar proposals have failed to advance in the Michigan Legislature.

Shoppers can consult databases like EPA Safer Choice, or look for products that claim to be PFAS free. But with thousands of compounds in production, it’s difficult to avoid the chemicals simply by reading ingredients lists.

“Our system has made it so that the onus is on individuals to solve this,” Bloom said. “And that's just wrong.”

Bloom believes deeper reforms are needed. The US should join states like Minnesota in banning nonessential uses of PFAS, she said, and stop approving new chemicals without thorough safety vetting. By law, the US Environmental Protection Agency must review chemicals before they hit the market, but environmentalists have long complained that the process lacks teeth.

“We really need a more comprehensive look at how we're regulating chemicals in our state and in the country,” Bloom said, adding that “there just shouldn’t be toxic chemicals in any products.”

While residents debate where Cadillac’s contamination came from, and whether public officials responded appropriately, all seem to agree on one thing: The situation has raised awareness about the risks that can come from using a private well in the era of PFAS.

“I’m asking my grandparents about their well,” said Galvanek, of Cadillac Advocates for Clean Water. “I’m speaking to my cousins and my neighbors. I’m speaking to my friends and coworkers, and just saying ‘Hey, have you had your well tested?’”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!