Michigan is the king of potato chips. But a disease is killing state spuds

- A worm-and-fungus disease kills up to half of Michigan’s potatoes every year

- Currently, farmers protect their crops by spraying chemicals

- MSU researchers believe a mix of special manure and compost could work just as well, and is better for the soil

Michigan is the nation’s leading producer of potatoes for potato chips, and potato farmers across the state harvest 1.7 billion pounds annually.

So it’s concerning that, by July of any given summer, up to half of the state’s potato leaves begin to wilt, their stems harden and they will slowly die if left untreated.

These are the first effects of potato early die complex, an infectious disease that poses a threat to some 46,000 acres of potatoes in Michigan. If not treated, the disease can cost family businesses like Walther Farms, a commercial potato farm based in Three Rivers, up to $500 per acre.

Related:

- Michigan health care reimagined using dirt, worms and fresh veggies

- Michigan farmers using too much fertilizer, hurting water quality efforts

- Talking Detroit’s Eastern Market, the hunt for the Michigan potato, and other food stuff

“Every time we plant potatoes back on a field that’s had potatoes…on it before, then early die risk increases,” said Karl Ritchie, agronomist for Walther Farms. “So, it’s only going to get harder from where we are right now.”

But Michigan State University researchers, armed with a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, hope that a special blend of manure and compost will limit the spread of early die complex, without the use of harmful chemicals.

The blends are a more sustainable “investment in time” in improving soil health, said Marisol Quintanilla, lead researcher and assistant professor at the MSU Department of Entomology. The fumigants currently used are short-term treatments that produce a quick and beneficial return but may reduce soil quality over years of reapplication.

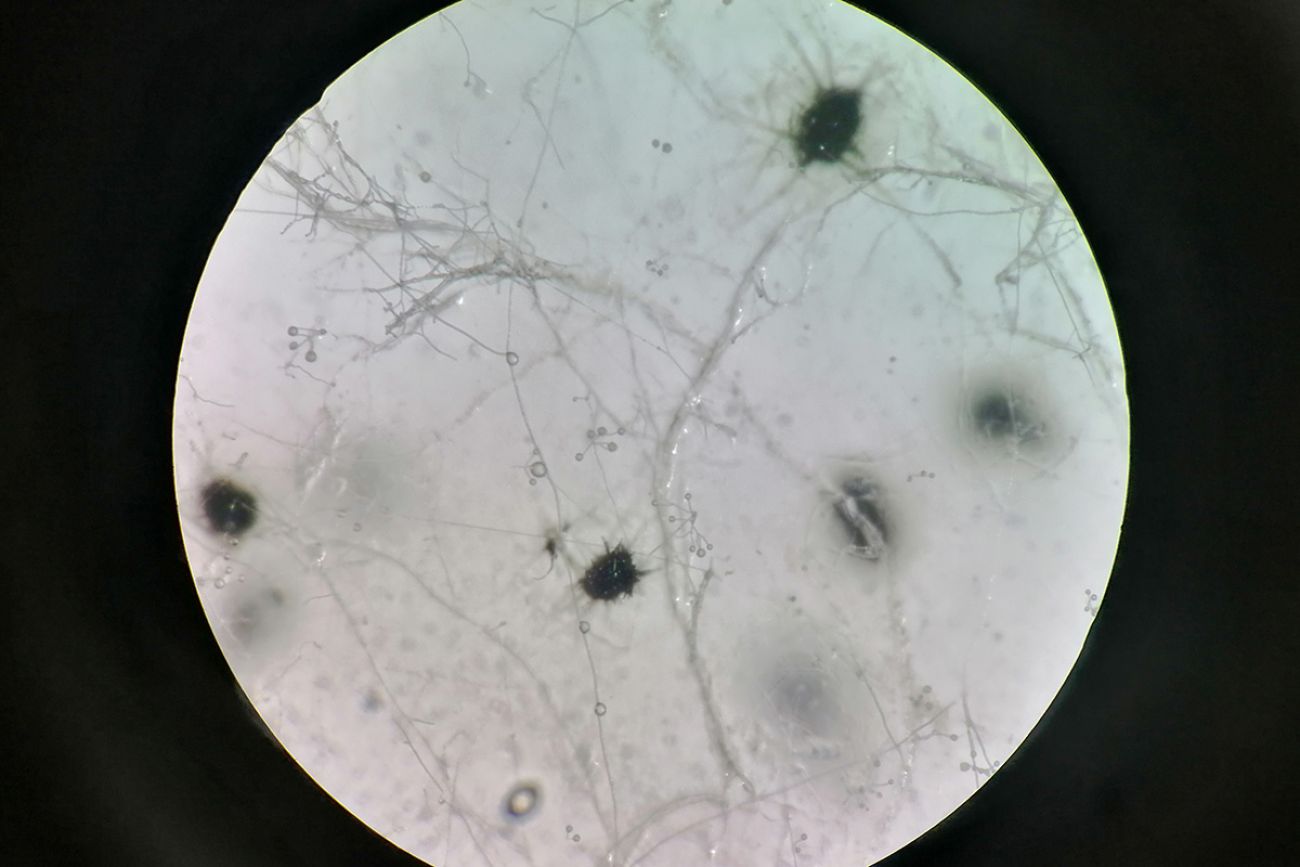

Early die complex has been bedeviling researchers in Michigan since the mid-1970s. The disease is the work of root lesion nematodes, microscopic worms, and verticillium dahliae, a fungus — organisms that work collaboratively to kill potato plants.

“There’s a synergistic reaction when they’re together,” said Mark Otto, president of Agri-business Consultants in Lansing. “When they’re together, they’re worse than either one separately.”

After potatoes are planted in early May, nematodes make the plants more vulnerable by penetrating the potato’s roots within the first weeks. Verticillium then plugs the wounds the nematodes dig, preventing nutrients from traveling from root to plant, Ritchie said.

The compost and manure blends suffocate and kill the nematodes, Quintanilla said.

In previous research led by Quintanilla, a blend of chicken manure, cow manure and wood ash compost was found to be the most effective to reduce potato early die complex, said Abigail Palmisano, graduate student at the MSU Applied Nematology Lab.

At Walther Farms, roughly half of the business’s 8,000 acres in Michigan are currently sprayed or injected with pesticides into the soil before the potato planting begins, Ritchie said.

The chemicals can kill 70 percent of potato early die, but it’s a costly method at $250 per acre at Walther Farms.

Ritchie said pesticides are all too common in farming, but farmers would “like to be using the least amount” they can get by with. A biological alternative that is as reliable, affordable and easy to use as fumigation is ideal.

For plants infested with potato early die complex, fumigation kills the nematodes, giving the plant a one-week head start to the growing season in June, compared to untreated plants. But research found the microbes eventually rebound, with the good microbes regrowing first in August and bad microbes in reduced numbers, Ritchie said.

Ideally, the potato’s foliage should remain green until mid-September, said George Bird, professor emeritus in the Department of Entomology at MSU. When potato early die strikes, the plants begin to wilt and fade in mid-July. Farmers isolate the affected potatoes from the unaffected to avoid spreading infection, according to Kelly Turner, executive director of the Michigan Potato Industry Commission.

Using micro plots, sets of smaller soil test plots, MSU researchers will test for bacteria or fungi that may affect nematode growth. After planting in June, they will apply the manure and compost blends one week later. When harvesting in the fall, researchers can learn which mixture of soils most effectively reduced disease. They’ll allow the soil to sit through the winter, then repeat the trial to see if the compost or manure blends remain effective.

The research’s goal isn’t to eliminate potato early die; that’s considered not realistic, said Luisa Parrado, an MSU doctoral student working on the project. But researchers hope to develop an eco-friendly method that will eliminate the damage to local growers.

“We are confident because we have seen positive results,” Quintanilla said.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!