Wind wars: Wind turbines put green energy on the ballot in mid-Michigan

- Wind and solar farms are expanding in Michigan to decrease reliance on carbon fuels. They are often sited on farms.

- Opponents fear wind turbines will lower property values or cause health problems

- Michigan’s utility companies and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer have ambitious wind and solar energy goals

MONTCALM COUNTY — John Black is the fifth generation of his family to farm the clay and sandy soil in Montcalm County’s Winfield Township, with the sixth and seventh generations working there now, too. He has 340 head of dairy cattle and 700 acres of hay, soybeans and corn, some planted along Black Road, named for his ancestors.

But now, as the 58-year-old steers his Ford truck along a dirt road past massive potato fields, he barely recognizes his community.

Township board meetings, where attendance in the past could be counted on one of Black’s calloused hands, now regularly devolve into shouting matches. Some residents have stopped talking to neighbors. In a community where many have lived for generations, the word “distrust” is thrown around a lot.

Tensions are growing here between Michigan renewable energy advocates — including developers and some farmers — and residents who chafe at the prospect of large turbines or expansive solar farms near their homes

Some see renewable energy projects as a key to energy independence. Others lament that wind turbines are an affront to their Hallmark-worthy rural communities, and worry, with sometimes disputed facts, that the projects — some of which spread over hundreds of acres and can be seen for miles — could cause health problems and lower property values.

For now, Ground Zero for that fight is mid-Michigan’s Montcalm County, where angry residents have seemingly out-organized and out-messaged a wind energy developer with a record of successfully completed projects around the country.

The fate of wind power in Montcalm may be decided Nov. 8, when citizen-initiated referendums over wind energy will be decided in four townships, and at least a dozen township officials who’ve supported wind energy face recalls.

Among those facing recalls: Winfield Township Trustee John Black.

“I’m flabbergasted by what has happened the last two years,” Black said. “I think I’m almost to the point where I’m roadkill along the side of the road.”

Whatever happens, grassroot efforts by a group of Montcalm citizens are both a model for other Michigan residents unhappy about potential projects in their backyards, and a harbinger of the challenges Michigan faces as it rushes to increase renewable energy production in the state.

“There’s a tried and true playbook for defeating these projects in Michigan,” said a frustrated Albert Jongewaard, senior development manager for Apex Clean Energy, the developer of the proposed project in Montcalm County. “Give them credit, they’ve done a great job.”

‘Go faster’

The tensions in Montcalm County are an example of the challenges Michigan and the country face as renewable energy expands. Wind and solar projects take lots of space, and that space is almost inevitably in rural areas. Residents in those areas tend to be politically conservative and feel strong ties to the land. Many are not happy to bear the brunt of the green revolution.

That unhappiness is flaring up across the nation, but experts say the fights are more frequent, organized and impassioned in the “Pure Michigan” that people are familiar with in tourism ads.

There are 34 currently operating utility-scale wind turbine farms in Michigan, from Hillsdale County near the Ohio border to Delta County in the Upper Peninsula. The majority are clustered in the Thumb counties of Huron, Tuscola and Sanilac, and in mid-Michigan, noticeable to travelers along U.S. 127 in Gratiot and Isabella counties, which border Montcalm.

In 2021, renewable energy sources provided about 11 percent of Michigan’s net electricity generation, with most of that (77 percent) coming from wind. There are 1,658 turbines across the state churning out 3,527 megawatts, enough electricity to light at least 1.4 million Michigan homes last year.

That’s enormous growth in a short amount of time. The amount of power produced by renewable sources in Michigan has jumped 77-fold since 2010, and an additional three wind farms and three solar parks are expected to be running by year’s end.

Even so, wind and solar energy production is nowhere near what state and national officials hope to attain soon. Consumers Energy and DTE both have set goals of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The Biden administration set a national goal of 100-percent carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer introduced a plan to generate 60 percent of the state's electricity from renewable resources and phase out coal-fired power plants by 2030 — seven years from now.

Just replacing Michigan’s seven coal plants (two operated by DTE, five by Consumers), which now provide nearly a third of electricity for the state, will be a monumental task.

For example, according to a Consumers Energy spokesperson, the utility company’s largest coal plant, located in West Olive in Ottawa County, can generate 840 megawatts of electricity. Replacing the energy produced from just that one of Consumers’ five coal plants would take about 336 turbines. To replace that coal plant with solar power would take 13 square miles of solar panels — twice the land size of Montcalm’s largest city, Greenville.

“We need to be going at a faster pace (to meet the state’s 2030 goal), and we need to find ways to do that,” said Corey Connolly, climate and energy advisor for the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy. “And when I say we need to go fast, we need to go fast.”

Power or paradise

Sheila Crooks remembers feeling her heart pounding in her chest as she walked to a stranger’s door for the first time to talk about wind turbines. She’d never been involved in politics, never spoken in public, never attended a township meeting.

Crooks had always lived a quiet life with her husband on 78 acres in rural Douglass Township in Montcalm County, about 20 miles from Black’s farm. Their one-story home is back a long drive, past an alfalfa field, past a small pond, and up a hill and into woods thick with oak and deer.

In the summer, Crooks tends to flowers in containers around the outside of the home and her husband hunts for turkey in the woods. When nieces and nephews come over, they fish for bluegill in the pond, and Crooks fries them up for supper.

But in the fall of 2020, Crooks saw a threat to that serenity. Outsiders were coming to this placid patch of lakes and potato fields and, in Crooks’ view, threatening to ruin everything.

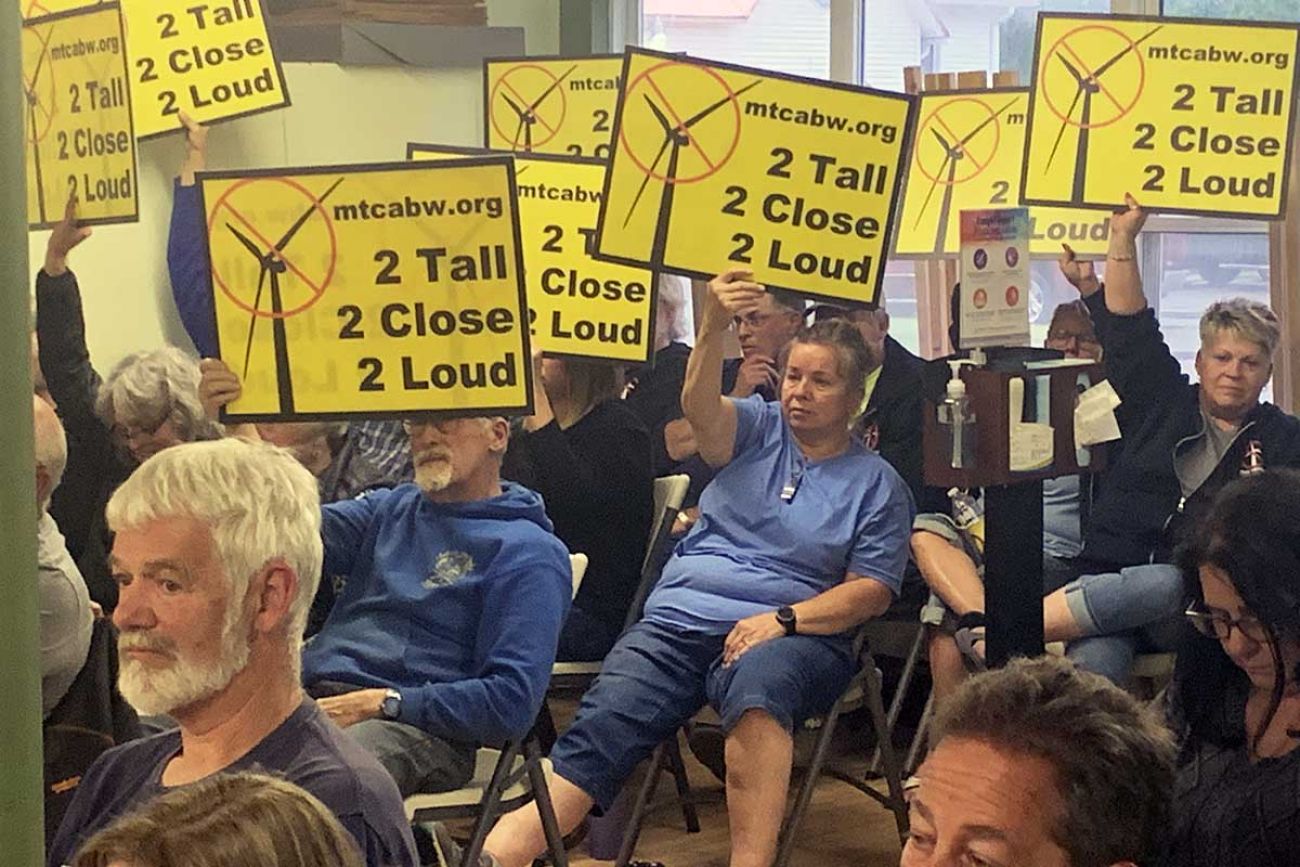

Now, the 58-year-old attends not only meetings in her own township, but in a half dozen others, holding up a sign that says “2 tall, 2 loud, 2 close,” and joining others in rebuking township officials who speak positively about the proposed wind energy project that could place dozens of turbines, each as tall as a 60-story building, in farmland around the county.

Some of those turbines could be within a mile of her property.

“You start putting these pieces together, and you realize you’re being preyed on because you’re a poor township that happens to be close to transmission lines,” she said.

Montcalm County is in the heart of Michigan’s potato chip belt. A quarter of potato chips in the United States start as spuds in Michigan fields, many grown in Montcalm and surrounding counties. There is a potato festival in the Montcalm village of Edmore every September, complete with the naming of the potato queen and a potato meal drive-thru.

Beyond potatoes, the county is most known for its 55 lakes, with 28 larger than 50 acres.

“I live on a lake in Sidney Township,” attorney Robert Scott said. “Everything is green, you have rolling hills. It’s an ideal place to live.

“I had no desire to live anywhere else, up until Apex rolled into town.”

Scott and Crooks sat around a kitchen island at a rural Montcalm County home with three other anti-wind advocates recently. They say they’ve been called Nazis, terrorists, bullies and, in Crooks’ case, just plain crazy.

They said they’d never been politically active in the past. One is a lawyer, another an engineer, another a retired labor negotiator. They didn’t know each other before 2020, when they heard through social media that a developer was trying to gain permission from local township boards to erect wind turbines.

In October 2020, one concerned resident set up a Facebook group, called Montcalm County Citizens United, to share information about the proposed project. Weeks later, more than 100 residents showed up to a meeting at a township park, peppering Apex representative Jongewaard with questions about the plan.

“We all came away very skeptical of what was being planned,” Scott recalled.

More residents joined the Facebook group, sharing information. Several townships had already approved ordinances that would allow wind turbines to be erected, they learned. (Some of those plans have been walked back, under pressure from residents.) Several officials in various townships who were considering approval of wind ordinances had already signed leases for their home property with Apex.

“I started just wanting them away from my house,” Crooks said. “Then I started going to meetings, and … you start hearing the deception and the twisting of the information, and you start realizing you don’t want these people anywhere around your community.”

The anti-wind Facebook group grew to more than 3,000 members, with residents posting memes about the dangers of wind turbines and the dates and agendas for township meetings. Signs sprung up in lawns protesting wind turbines. Residents bought matching T-shirts to wear to meetings, where they’d roar their approval for those making anti-wind statements, and, on occasion, shout down those who spoke in favor of the project.

At a June meeting, about four dozen wind turbine opponents filled the one-room Winfield Township Hall for a trustee meeting at which the board was scheduled to approve a wind ordinance that would allow turbines. Speakers cited what they believed to be the dangers of turbines, both for health and for property values. Several speakers referenced the Bible and suggested trustees who vote to allow turbines aren’t following God’s will. People held large yellow signs above their heads. Some shouted at trustees, and the township supervisor, a woman who is nearly 80, yelled back.

In the end, the board rejected the ordinance and sent it back to the township planning commission for more work.

“Basically, they yell at us for everything,” Black, the farmer and trustee, said later. “They say ‘You’re listening to Apex. You’re going to kill the worms, you’re going to contaminate the groundwater, you’re going to kill all the birds, you’re going to drive all residents out of the township and kill property values.’

“You come home from a meeting and … you feel all twisted up,” Black said.

Tall, and getting taller

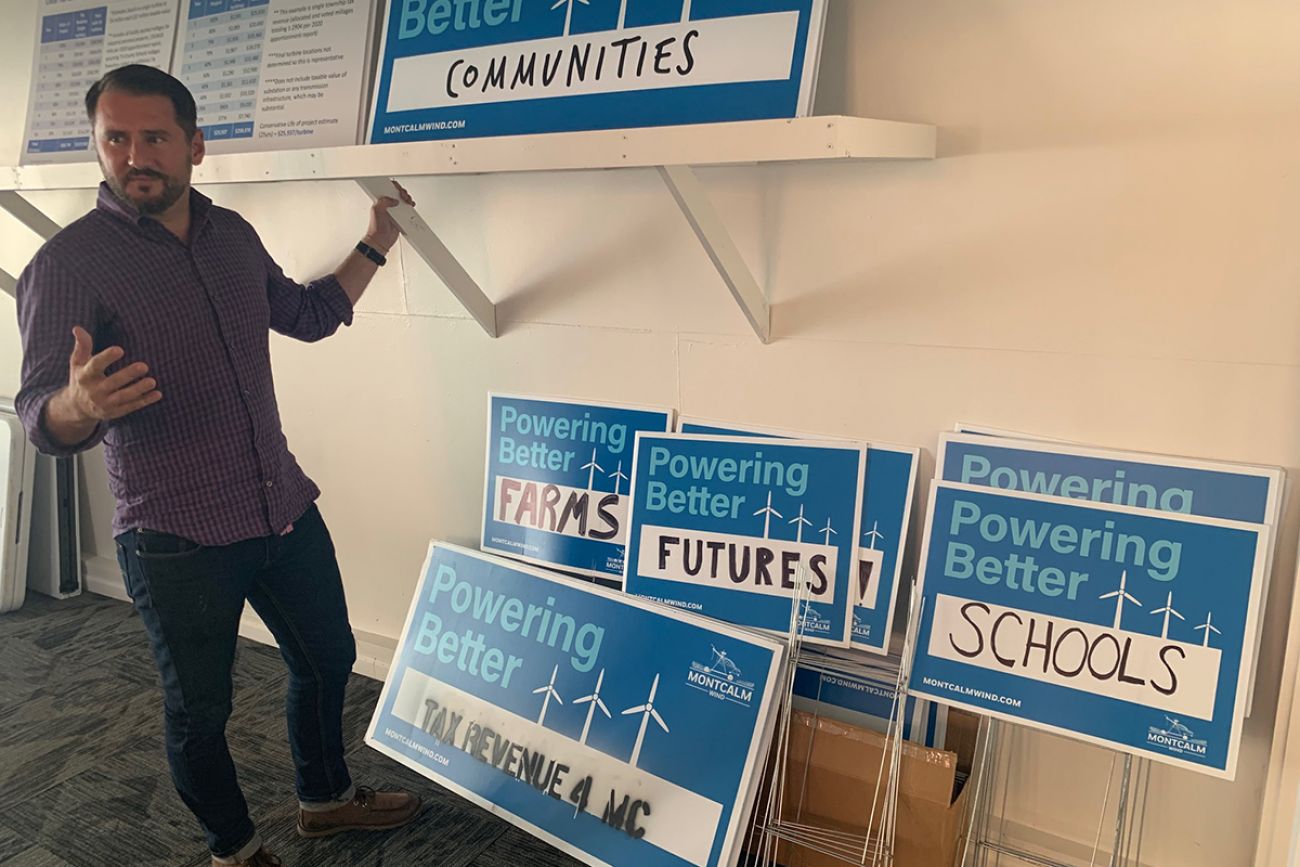

The Montcalm County office of Apex Clean Energy is located in a nondescript building that once housed a convenience store and a butcher shop in the village of Trufant. Inside, there are yard signs promoting the community benefits of a proposed wind farm — tax revenue for schools, roads and local governments.

In charge of the office is Jongewaard, a 39-year-old from Minnesota who travels around the Midwest trying to get wind and solar projects off the ground. Apex, which is based in Charlottesville, Va., was the developer of a wind project in neighboring Isabella County where turbine blades started turning in 2020. Jongewaard started making house calls to Montcalm farmers before that project finished.

He talked to the farmers about leasing land to Apex for turbines, and began cultivating relationships with local officials in the county of 64,000.

There had been little pushback in neighboring Gratiot County to a sizable wind farm. Some of the 499-foot turbines were within a few miles of the Montcalm County line. The company hoped to erect even taller structures in Montcalm. Jongewaard told Bridge Michigan his preferred height would be 656 feet from the ground to the tip of a blade at its peak. Taller turbines can generate more power, meaning there wouldn’t have to be as many of them in a wind farm.

At that height, the turbines would be 100 feet taller than the Washington Monument, and more than double the height of the Statue of Liberty.

Some Montcalm residents were angry over the proposal. And in Michigan, local sentiment matters on energy policy.

In the Midwest states of Ohio, Wisconsin and Minnesota, site approval for utility energy projects is done at the state level. But in Michigan, projects are approved by individual township planning commissions and boards of trustees. The result: Projects like the one in Montcalm valued at tens of millions of dollars that can impact energy statewide must gain the votes of farmers and small business owners serving on township boards.

Apex originally wanted to build turbines in parts of 11 townships in Montcalm County, which meant more than 20 boards needed to sign off on turbines within their borders. While Apex didn’t need turbines in all the townships to be successful, they needed a critical mass.

On one side of the battle were farmers like Black, who hasn’t signed a lease but said he would consider it, who argues that the more than 300 residents who have signed leases should be able to have wind turbines built on their land if they want. According to a draft lease offered to Black, those who sign can get $35 per acre per year for all leased land if the project gets up and running, plus $3,300 per year per megawatt produced by any turbines erected on their land. Turbines typically produce between 2.5 and 5 megawatts of power.

If several large turbines were sited on his property, Black estimates he could earn up to $50,000 a year from a wind energy lease. It’s not life-changing money, he said, but “it would make a payment on a new tractor.”

On the other side were residents who stand to gain little or nothing financially from turbines, but who would be able to see them from their back decks.

Often, the two sides seem to operate with different sets of facts.

“You can’t listen to the wind developer, because they’re the most conflicted person in the room and the most to gain,” said Montcalm resident Tim Thornhill, who defeated a pro-wind trustee in Maple Valley Township in the primary. “They come in with their snake oil and try to pull the shade over our eyeballs, but we can think. You can learn anything you want online.”

To Jongewaard, though, the information about the dangers of wind turbines residents were finding online and citing as facts at township meetings — such as epileptic seizures from blade shadow flicker and worms dying from vibrations — was “based on a lot of misinformation, it’s based on fear.

“It’s impossible to address all those things in a three-minute comment period,” he said. “As you start addressing one thing, more things get thrown on the wall like spaghetti, and you can’t clean up the kitchen fast enough to address all the issues in a real sense.”

In reality, the truth behind concerns raised about wind turbines is often more nuanced than either developers or anti-wind protesters acknowledge. For instance:

Do turbines drive down property values? Critics say they worry their homes will be worth less if their scenic views are marred by wind turbines. A 2013 study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California found no negative impact on the value of homes near turbines. A 2016 study published in the Journal of Real Estate Research found “no unique impact” on sales near turbines in Massachusetts, but did find a negative impact on values of homes near major roads or transmission lines.

Here in Michigan, though, an analysis of property values conducted by the Daily News, a newspaper covering Montcalm County, found some possible impact. According to Michigan Association of Realtors data cited in the Daily News report, average home sale prices have jumped 87 percent since 2013 in turbine-heavy Gratiot and Isabella counties. But over the same span, home sale prices in turbine-free Montcalm County rose 136 percent, and by 109 percent in the state overall.

Do turbines kill birds? It’s inevitable that birds and bats will sometimes strike wind turbine blades, which are more than 100 feet long and can weigh more than two tons. Among the victims: eagles and other large birds of prey. In April, NextEra Energy pleaded guilty in federal court to criminal violations of wildlife protection laws after its wind turbines killed at least 150 bald and golden eagles in eight western states. In that case NextEra disregarded recommendations from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service about siting of turbines to limit bird kills.

Up to an estimated 1 million birds are killed each year in collisions with wind turbines, according to the Sierra Club. That seems like a lot, but it pales in comparison to the estimated 6.5 million killed in collisions with communications towers, 25 million with power lines, 1 billion from windows and as many as 2.4 billion in the U.S. alone from encounters with cats.

Can turbines catch fire? A quick Internet search can turn up scary photos of wind turbines engulfed in flames. Turbine rotors contain a supply of oil, and do occasionally catch fire, but it is rare. Each year, about one in 2,000 wind turbines catch fire from mechanical problems or lightning strikes. For Michigan, with close to 1,700 currently operating wind turbines, that would mean an average of under one turbine fire per year.

Are turbines too loud? According to General Electric, a manufacturer of turbines, from 1,000 feet away, the sound from turbines is generally just over 40 decibels, which is the noise level of a refrigerator.

But critics point out that the sound isn’t steady — turbines make a whooshing sound as the blades rotate — and the noise continues day and night. “We don’t live in cities, so it’s dead quiet at night,” said Crooks, the resident fighting the wind farms. “That’s why we live here. They say it’s like a truck driving by. Well, I don’t have a truck driving by in the middle of the night.”

Are TV and cell phone reception disrupted? If you use a TV antenna to capture the signal from nearby TV stations, your reception could be impacted by nearby wind turbines. The same goes for local radio stations. But turbines shouldn’t impact cell phone reception, or cable or satellite TV signals.

Do turbines lead to health issues? Some people who live near wind turbines complain of headaches and trouble sleeping. Also of concern is “shadow flicker” — the shadows created as turbine blades pass in front of the sun. Some believe shadow flicker can cause nausea or epileptic seizures. But a 2015 analysis of 25 studies found no links between turbines and health problems of nearby residents.

Crooks still has her doubts that turbines are safe. “They’ll always say there’s no direct link to health problems,” she said. “That’s because some of the health problems come from sleep deprivation. It’s not a direct link, but sleep deprivation causes a lot of things.”

Farmers versus Lakers

The divide between farmers and non-farmers is what makes Michigan’s renewable energy battles more extreme than in many states, said Sarah Mills, senior project manager for the Graham Energy Futures Initiative at the University of Michigan. Mills conducted a study of wind projects in four Midwest states including Michigan, titled “Farmers versus Lakers,” that found “natural amenities” such as lakes near a proposed utility wind energy project increased opposition.

In essence, pretty much anywhere people have lake homes, residents don’t want turbines, some of which are taller than the main towers of the Mackinac Bridge.

States where wind energy has grown the fastest — including Iowa, where 58 percent of energy now comes from wind, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas — have great expanses of wide open spaces with few natural amenities.

Michigan, on the other hand, has about 11,000 inland lakes, not to mention that it borders four of the Great Lakes.

Wind projects “have gotten more opposition over time (because) projects have gotten closer over time to areas where you would expect opposition,” said Mills of U-M. “The low-hanging fruit (areas) have been developed; now, they’re going to areas where there are a mix” of large farms where renewable energy projects have been built in the past, and more populated areas.

In a series of focus groups about wind farms conducted by researchers at Macalester College in Minnesota, Michigan residents expressed concern that wind farms could disturb the “pristine” and “peaceful” elements of what Michiganders refer to as “Up North.”

Mills found similar results. “Based on my survey data, the projects in Michigan tend to be slightly more contentious,” Mills said. “It’s not that there’s something about Michiganders. It’s that we have a lot of landscapes where people have vacation homes.”

Adding to the challenge of renewable energy expansion is the siting of wind and solar farms in rural communities that are predominantly politically conservative — among people who tend to be skeptical of green energy and the people who promote it.

“Climate and energy development is intensely politicized,” said Bradley Pischea, deputy director of the Land and Liberty Coalition, an organization that supports utility-scale renewable energy projects. “And now you have developers coming into rural red communities and (residents) being told this is a good thing, when they believe it’s a fad, it’s posturing, it’s unreliable.”

Pischea’s group encourages developers to downplay climate change and sell wind and solar projects as drivers of economic development in communities like Montcalm County, which ranks 55th among Michigan’s 83 counties in median household income.

There’s little doubt about the positive economic impact of renewable energy projects. An Upjohn Institute analysis prepared on behalf of the Montcalm Economic Alliance, a branch of a Grand Rapids regional economic development organization The Right Place, concluded that the proposed wind project could, over 30 years, provide $118 million to leaseholders in the county and $80 million in payments to units of government, including county schools, Montcalm Community College, the sheriff’s office, libraries and the operating budgets of the townships and county.

“We feel strongly that we can be climate agnostic and still make a case that this is a better thing for these communities,” Pischea said.

Making that type of sales pitch is about all state officials can do – they have no authority to approve development of utility projects because land development decisions are left to counties and townships, an extension of the state’s “local control” philosophy.

The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) offers education, training, planning and technical resources to local officials about renewable energy, as part of the state’s MI Health Climate Plan.

It’s not always an easy sell, acknowledged EGLE Director Liesl Clark. “There's just a deterioration of trust that I think is a real challenge,” Clark said. “You can see it nationally and you can see it play out in so many contexts right now.

“I know that it's there,” Clark said. “(But) I also think that the good news is because of the economic development opportunity and the jobs opportunity that comes with (renewable energy), let alone the vital climate reasons for doing these things, … it creates an opportunity to really move things forward.”

It may be too late to make that pitch in Montcalm, where several renewable energy proponents — and one referendum — have already been defeated.

A referendum to approve solar power guidelines in Winfield Township was smacked down in a landslide in the August primary, 71 percent to 29 percent, and three pro-wind incumbents lost to anti-wind challengers the same day. A trustee in Sidney Township who supported the wind project was recalled by a more than 2-1 margin in May.

“Apex lost the PR war,” said Black, the farmer and Winfield Township trustee. “I get it, it’s not a campaign, but it’s politics.”

Picking sides, losing friends

Whatever the outcome Nov. 8, community relations in what many describe as a once close-knit community have crumbled. Anti-wind residents accuse pro-wind neighbors of being “corrupt,” while those who support renewable energy projects in the county say the anti-wind folk are spewing lies.

Most who spoke to Bridge said they have lost friends in the fight.

“We all know each other, we all respect each other,” anti-wind resident Thornhill said. “It was like living in a family. And all of a sudden people were divided against each other.”

Jongewaard, of Apex, said “we’re seeing a lot of these farmers being vilified. Suddenly, they’re the bad guys and they’ve been out there working all their lives, not taking vacations because they’re milking cows at 4:30 in the morning 365 days a year. Those folks have rights, too.”

But those farmers now appear to be in the minority in a county where many voters are more familiar with pontoons than plows. “Ugly is not the only reason (to oppose wind farms), but it is a reason,” said Scott, the attorney and lake home owner. “People say you should support a compromise, (but) we don’t want them here at all!”

Even before Tuesday’s election, Montcalm’s grass-roots anti-wind campaign has had success hobbling the wind development. Some townships initially receptive to wind energy have since backed down. Four townships (Pierson, Sydney, Pine and Eureka) passed wind turbine ordinances so restrictive (such as requiring large setbacks from roads and other property and limited turbine height) they amount to virtual bans.

The anti-wind group hopes to build on those victories Nov. 8 with defeats of referendums in four townships, and the recall of pro-wind officials in several. “Vote No” signs are posted around the county, some listing the names of preferred anti-wind candidates.

One possible lesson to be learned by state and local officials who support the expansion of renewable energy: talk to residents early and often about the pros and cons of projects — something that residents say didn’t happen in Montcalm.

“The joke is that it's 50 cups of coffee per megawatt, because you've got to be talking to community members,” said EGLE Director Clark. “The work that we do has got to be community focused first and foremost. Everything we do has got to start with the residents of Michigan in mind.”

‘This transition is happening’

Apex’s Jongewaard said he isn’t sure what the company will do if the wind proposals are defeated on Nov. 8. The company could go to court, arguing that referendums and ordinances that restrict the right of property owners to develop their land are illegal. Or Apex could pull up stakes and move on to other communities where they may face less opposition.

But there’s one thing Jongewaard feels certain about: Opposition to renewable energy may slow the spread of wind and solar projects in Michigan, but it won’t stop it.

“This transition is happening,” he said. “These projects are good for farmers, and for local communities. And frankly it’s good for the planet.”

Pischea, of the renewable energy coalition, said it’s important not to read too much into the success or failure of any one project.

“If you're batting over .300, you're probably doing pretty well,” Pischea said. “A lot of these developers are coming into communities and trying to acquire as much land as possible and seeing what works. A lot of projects don’t move past that early stage.”

In fact, even as Apex continues to fight for the wind project, the developer and Consumers Energy have been talking to Montcalm landowners about possible solar park projects in recent months.

Black, the Winfield Township farmer and trustee, has received several solicitations to put solar arrays across his fields. But even if he were interested, he couldn’t do it, because in August the township voted down a referendum to allow utility-scale solar farms.

He’s also come to terms with the likelihood he’ll be recalled from his trustee post and replaced with an anti-wind candidate on the November ballot.

Black said he’s enjoyed the job, it gives him a way to get to know neighbors. But the $100 a month he gets isn’t worth the grief he receives from anti-wind residents who call him corrupt. One township resident who used to attend the same church as Black suggested the trustee was a sinner. That one stung.

“This is still an awful nice community,” he said. “And I think most rural communities are like that.

“My dad died quite young, I had to take over the farm when I was 30, during corn harvest. One morning I was milking cows and the combines started rolling in, and my neighbors harvested my whole crop in one day.

“That is the community that I know,” Black said, his voice breaking. “It’s not the one I go to the township meeting where all this malarkey is being said.”

For Montcalm residents, there remains a question of what happens to the community once the wind wars are over.

“I think it depends on how it ends,” said wind critic Rodney Nutt. In his view, peace returns only when renewable energy developers leave Montcalm.

“How do you not feel destroyed if your neighbor has to move because they have physical effects from wind turbines," Nutt said, “especially when you know the people who pushed it are the people getting the monthly checks?”

Crooks said she isn’t sure when or if she’ll again talk to neighbors who “don’t care enough” to fight the wind project. She plans to keep attending township meetings to be better informed. And if she has to knock on more doors, she’s ready.

“We still have a lot of work to do,” she said. “It’s the biggest issue that will ever hit our little township.

“We’re fighting a Goliath here, and we’re David.”

Black never pictured himself as Goliath, but he’s resigned to the likelihood that wind or solar projects are unlikely in Montcalm, at least for now.

“Personally, I feel defeated about this whole project,” he said. “I don’t know if other places are this divided. But if the CEOs of Consumers and DTE don’t realize it, they’d better soon, because I don’t know where they’re going to put their renewable energy.”

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!