Congrats on budget, Michigan. It does little to fix state’s biggest problems.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was updated Dec. 11, 2019 to reflect legislative budget transfers on Wednesday morning]

LANSING – At long last, Michigan’s divided government has the framework for a budget deal. But it’s mostly flat and doesn’t include major funding to big problems voters elected lawmakers to solve.

This week's agreement to end a months-long standoff includes just $13 million in extra money for crumbling roads and bridges that experts say would cost billions to improve.

Education funding for struggling schools? Still lagging the nation.

Money for colleges whose tuitions have soared as state aid fell? Flat.

One notable exception: Lawmakers are stepping up money to combat environmental hazards, especially those creeping into state waterways from PFAS chemicals.

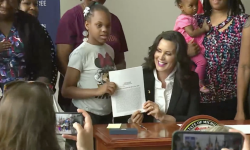

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and GOP leaders touted the deal over the $58.9 billion budget as an important resolution to a contentious process, but Democrats and Republicans remain divided over whether more money can solve the state’s problems.

Michigan Republican Party Chairwoman Laura Cox praised the deal and accused the Democratic governor of using people as a "bargain chip" in her quest to raise fuel taxes.

“I am happy to see that so much funding was restored to Michigan’s most vulnerable citizens and communities,” Cox said in a statement.

Gilda Jacobs, a former Democratic lawmaker who now serves as president and CEO of the Michigan League for Public Policy, suggested state officials can’t address critical needs unless they increase taxes or find other ways to generate new revenue.

"Political infighting over process, priorities, shell games and funding streams—and more importantly, the struggles facing our kids, our workers and our seniors—could all be resolved with bold and courageous leadership to bring in new money and invest in what the state really needs," Jacobs said in a statement.

Bridge Magazine has tracked Michigan’s problems for years, and the budget stalemate for months.

Here’s a look at seven vulnerable areas in Michigan and comparisons of what studies say should be done and how the budget battle played out.

Roads

State of affairs: Michigan roads routinely rank among the worst in the nation, and the budget won’t do much to improve them. Whitmer won office last year on a campaign to “fix the damn roads,” but her proposal to raise fuel taxes 45 cents per gallon was dead on arrival this year.

Former Gov. Rick Snyder’s 21st Century Infrastructure Commission projected the state needs at least $4 billion more per year to maintain and improve crumbling roads, bridges, water systems and communications infrastructure. Bad roads cost Michigan drivers an average of $648 a year in vehicle repairs and other related costs, according to research from a group partially funded by road builders and engineers.

What Whitmer proposed: Her first budget proposal was built on a plan to raise Michigan’s 26.3-cent per gallon fuel tax by 45-cents over the next two years, including two 15-cent increases during fiscal year 2020 that would have generated another $1.3 billion. Once fully phased in by 2021, Whitmer’s gas tax would have increased state revenue by $2.5 billion a year. She proposed $2.1 billion a year in new spending on roads and bridges and wanted to put another $400 million toward schools and other budget priorities.

What the Legislature passed: The Republican-led Legislature never seriously considered Whitmer’s fuel tax plan and did not propose an alternative, despite earlier suggestions they would do so. Instead, lawmakers sent Whitmer a budget that included another $400 million in one-time spending for road and bridge repairs. Of that, $243 million was for repairs on four bridges in Dearborn, Ferrysburg, Harrison Township and Lansing that Whitmer had visited while making a public push for a fuel tax increase.

Final resolution: $13 million in extra money for roads and bridges, a tiny fraction of the state's total transportation budget, which will remain flat at about $5 billion for 2020.

Whitmer vetoed $375 million in one-time road funding from the Republican budget and used a rare transfer power to redirect the other $25 million toward local mass transit and rail projects.

As part of their deal with the governor, legislators on Wednesday used a more traditional transfer process to shift $13 million of that one-time money back into a budget line for "fixing Michigan roads and bridges." They used reserved transportation funds to replace the urban transit money.

The budget deal does not address long-term road funding needs, but leaders say they may resume those talks after dust from the budget storm finally settles.

K-12 education

State of affairs: Michigan’s public schools, once in the top 10 in the nation, are now average at best. Michigan ranks 28th in eighth-grade reading and math, 32nd in fourth-grade reading and 42nd in fourth-grade math. In the state’s standardized test, third-grade reading scores — an indicator of future academic success — are stagnant despite at least $80 million invested in early literacy.

Education leaders have focused efforts on early literacy as a key to turning around Michigan’s schools and, in the long term, increasing the share of adults with college degrees (34th in the nation).

Michigan is last in the nation for school funding growth over the last 25 years, and a group of business and education leaders released a report in 2018 recommending Michigan increase school funding to $9,590 per student, and provide additional funding for students with greater needs through a “weighted formula.”

What Whitmer proposed: Whitmer wanted to boost education funding by about $500 million and raise minimum foundation allowance funding to $8,051 per student. She also proposed another $31.5 million for literacy coaches and giving more money to districts for educating students who are in special education, academically at-risk or economically disadvantaged.

What the Legislature passed: The Legislature approved about $300 million in additional funding for education and increased the per-student foundation allowance allotment to $8,111 for the schools receiving the minimum level of funding.

Lawmakers did not include a weighted funding system but set aside around half as much money as the governor for special education and career and technical education. They allocated $21 million for literacy coaches and added $10 million for school security measures.

Final resolution: Whitmer vetoed $127 million in education-related programs, including a $35 million increase in funding for charter schools that would have matched the increase for traditional public schools, $7 million for isolated school districts and the money for school security. Republicans got those back in the supplemental deal, and Whitmer’s $31.5 million plan for literacy coaches won out.

Higher education

State of affairs: Going to college in Michigan is more expensive than in most other states. Higher education experts say that’s because state spending on public universities has declined over the last 20 years, pushing schools to raise tuition to cover the gap. A recent study found state funding per student has dropped 40 percent since 2000. College student debt has increased $10,000 in the past decade as Michigan families pay nearly 70 percent of the cost of college — the sixth-highest rate in the nation. In comparison, Illinois families pay 32 percent of their students’ public college costs.

What Whitmer proposed: The governor proposed a 3 percent across-the-board increase in operations funding for the state’s public universities — slightly more than recent higher education inflation estimates of 2.6 percent.

What the Legislature passed: Lawmakers approved a 0.5 percent increase in funding for higher education operations funding. They also increased funding for need-based tuition grants for private colleges from $2,400 to $3,000 per student.

Final resolution: Whitmer vetoed the private college tuition grant program entirely, which included $38 million in mostly federal funds. That money came back under the negotiated supplemental. The Legislature’s 0.5 increase in operations funding for colleges won out.

Early childhood education

State of affairs: Preschool helps kids succeed in school, make more money and even commit fewer crimes. Many more children have been able to access preschool through the Great Start Readiness Program (GSRP), which provides state-funded preschool to low- and moderate-income children. Child care and early childhood education is increasingly a challenge for many families. A 2017 report from Snyder’s administration recommended funding universal preschool statewide, which would cost around $400 million more annually.

What Whitmer proposed: The governor suggested adding $84 million to the GSRP program, raising funding to $329 million per year. She also proposed allowing more families to qualify, raising the eligibility threshold from 250 percent to 300 percent of the federal poverty level so families of four making less than $77,250 could qualify, and proposed raising the allocation per child.

What the Legislature passed: The Legislature increased GSRP funding by $5 million, for a total of around $250 million, and didn’t change the qualification threshold or per-child allotment. Lawmakers also maintained $2 million for training and added $50,000 for a study showing GSRP’s effects on kindergarten performance.

Final resolution: This one went untouched by the budget turmoil — the Legislature’s proposal, a small bump in funding that’s significantly less than what experts recommended, prevailed.

Environmental protection

State of affairs: Michigan is home to over 40 percent of the Great Lakes’ waters and more freshwater coastline than anywhere in the world. Michigan’s water is threatened by urban and agricultural runoff, invasive species and algae blooms. Michigan spends $1 billion less annually than it should on water and sewer infrastructure, according to the 21st Century Infrastructure Commission, and many communities face drinking water challenges from chemicals such as PFAS, which may have been discarded at more than 11,000 sites statewide.

What Whitmer proposed: Whitmer proposed a decrease in funding for the newly-named Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, but included $1.9 million for a new unit to implement stricter lead and copper rule requirements and add 14 new full-time positions for petroleum cleanup sites. She also proposed $120 million to help communities comply with the lead and copper rules, replace lead pipes, install water filtration systems in schools and research PFAS. In the Department of Health and Human Services budget, she proposed adding $5.5 million for PFAS response and $8.1 million for helping Flint residents exposed to lead.

What Legislature passed: The Legislature approved a nearly 20 percent increase in funding for the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy — one of the largest increases in funding for any department. Lawmakers approved many of Whitmer’s main appropriations in EGLE, and greenlighted Whitmer’s drinking water proposal totaling $120 million, including $25 million for PFAS remediation and $37 million for lead and copper rule implementation. Legislators did not approve her request for $60 million for filtered water in schools. In the DHHS budget, the Legislature approved $2.7 million for PFAS response and didn’t approve Whitmer’s additional funding request for Flint residents.

Final resolution: Most of the Legislature’s appropriations for environmental measures survived the veto pen. In addition, Whitmer added $7.5 million for private well testing to lead and copper rule implementation and $1.5 million for home lead abatement and $4.5 million more for lead paint remediation.

Medicaid

State of affairs: As of Monday, more than 651,900 lower-income residents were enrolled in Healthy Michigan, the state’s expanded Medicaid program largely funded by the federal government. Starting January, many will have to comply with new work requirements approved last year by the Republican-led Legislature. Debate over that policy re-emerged this year as the administration and lawmakers debated how much spending is needed to implement those new requirements.

What Whitmer proposed: The governor opposes the new requirement, which was signed by her predecessor, and used her budget to propose $26 million in new funding for implementation by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, including $13 million from the state’s discretionary general fund. Whitmer proposed another $10 million to provide workforce and training support to Medicaid recipients required to comply with the new requirements.

What the Legislature passed: In a series of largely party-line votes, the House and Senate approved a budget that did not include any of the work requirement implementation or training funding requested by Whitmer.

Final resolution: The state approved about $19 million of the $39 million Whitmer had proposed.

Urban affairs

State of affairs: Michigan’s economy has grown steadily since the Great Recession, but limited revenue options and property tax growth controls have slowed the recovery for municipalities. When adjusted for inflation, Michigan cities had 12 percent less revenue in 2017 than they did in 2002, according to a recent Public Sector Consultants report for the Michigan Municipal League. That means less money for local services like police, fire, elections and more.

What Whitmer proposed: Whitmer sought a host of increases in various revenue sharing programs, boosting total funding for local governments to $1.38 billion from $1.33 billion.

What the Legislature passed: Republicans passed a smaller increase to $1.36 billion.

Final resolution: Whitmer’s vetoes and budget shifts did not significantly impact revenue sharing payments to local governments, but she did cut several law enforcement programs that were ultimately reversed under the deal struck this week. The final budget agreement restored $14.8 million to reimburse counties for jailing felons who would have otherwise been sent to state prisons and $13 million for secondary road patrols by sheriff’s deputies. New funding includes $13 million for local transit agencies to meet match requirements for federal grants, $600,000 for an urban search and rescue task force.

Bridge reporter Ron French contributed to this report.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!