Screening tool gets second look amid bump in youth detention rates

LANSING — “Do you have a negative attitude toward the juvenile justice system?”

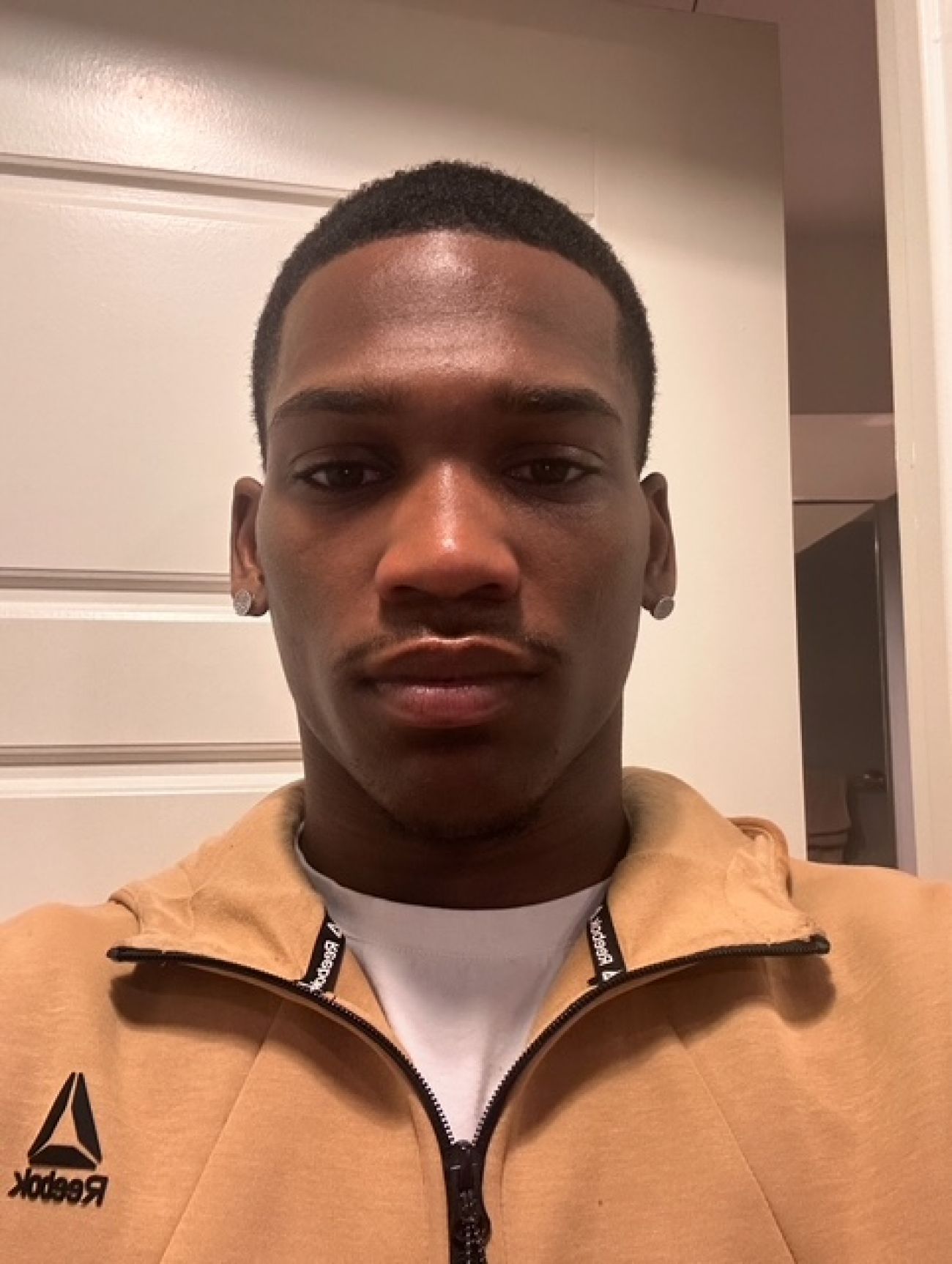

Questions like that may not sit well with an arrested youth, said former juvenile detainee Bilal Al-Raed of Grand Rapids.

But since last October, state law has required police to ask questions on such topics as part of a screening to determine whether youths are released or kept in custody at a juvenile detention facility until legal proceedings are over.

Experts say a well-designed detention screening helps divert nonviolent youths away from prison.

Related:

- Controversial youth detention tool goes live in Michigan. Is a fix coming?

- Critics fear reforms may boost incarcerations of minority youths in Michigan

- In Michigan, juvenile justice carries high cost: crippling debt for parents

- Michigan lawmakers vote to end most juvenile court fees, citing harms

But Al-Raed and other advocates for changes in the juvenile justice system say the current assessment queries may increase the likelihood of detention for youths of color.

“I spent a lot of time in detention and I’m still trying to recover to this day,” said Al-Raed, a representative of the Delta Project, a Grand Rapids-based youth justice advocacy group. “You’re isolated – it’s another form of trauma to go through.”

Youth detention screening was implemented statewide in 2024 after passage of legislation sponsored by Rep. Amos O’Neil, D-Saginaw.

But the detention screening tool that state court officials selected, the Ohio Youth Assessment System, has generated backlash from some advocates of youth justice — including O’Neil.

“We all noticed some changes that we need to make,” O’Neil said.

O’Neil and the state’s Supreme Court Administrative Office are collaborating with youth justice organizations to overhaul the assessment.

Meanwhile, family court administrators are evaluating whether a possible increase in detention rates may be tied to the screening tool.

The full impact remains unclear, said Ottawa County juvenile court director Thom Lattig, who is the president of the Michigan Association for Family Court Administration.

“I’ve heard that a couple other counties might be experiencing a small rise in detention placements based on the tool, but we’re still trying to pull together the data,” Lattig said.

Upon an arrest of suspects under 18, local law enforcement agencies are required to ask a series of questions.

Some queries are objective and have typically been used to make detention decisions before the screening requirement. Subjects include past offenses and the severity of the current offense.

Other topics include whether the youth has “difficulty controlling anger” or has a “negative attitude” toward the juvenile justice system.

The screening is used to categorize a youth as having a low, medium or high risk of reoffending. That label is used in conjunction with other details of the case to determine whether the youth is placed in detention.

The screening is intended to be done in-person, Lattig said, but not all law enforcement officers are trained to administer it.

In some localities, Lattig said minors may have to answer questions over the phone. If the screening isn’t completed, a judge will make a decision based on the youth’s record.

Jason Smith, the executive director of the Michigan Center for Youth Justice in Ann Arbor, said there are “major issues” with many of the questions, including one about family members’ histories of offense.

“We don’t think things like a family member’s arrest should be a determining factor in deciding whether or not a young person should be detained,” Smith said.

Lattig said a better screening method will likely take years of research to develop.

“The screening was never evaluated for Michigan needs,” he said.

“It’s a predictor of recidivism, that’s for sure. I just don’t know if it’s a predictor of which kids should go into detention or not,” he said. “I think the data will tell us down the road.”

Al-Raed said he sees the tool as a step back in the centuries-long process of reform in the juvenile justice system.

“When you’re implementing stuff into these systems, those people that it’s affecting don’t have a voice,” Al-Raed said. “I feel like that’s the most important voice that needs to be heard.”

Capital News Service originally published this article

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!