What Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's budget cuts and shifts mean to Michigan residents

Have a question about the budget?

Do you have a question about the Michigan budget? Email Capitol reporters Riley Beggin at [email protected] or Jonathan Oosting at [email protected]

and it could be the basis of a future story.

- Update: Five things to know as Michigan lawmakers kick-start state budget process

- Update: Michigan, we have a budget deal. (Give or take $400 million

- Update: Michigan Gov. Whitmer to GOP: I’ll make a budget deal, but won’t cede powers

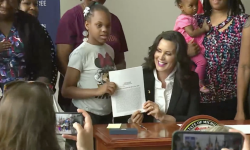

LANSING – Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer used a historic maneuver Tuesday morning to shift $625 million within state departments to reflect her priorities.

The dizzying changes could affect everyday Michiganders in ways large and small, from easing the transition to Medicaid work rules to providing more money for testing of lead pipes and buying better in-car cameras for the state police.

The changes come atop line item vetoes Monday that reduce spending on schools and roads by more than $500 million; eliminate the popular Pure Michigan tourism advertising campaign and include deep cuts for rural hospitals.

- Related: Republicans jockeying to override Gov. Whitmer’s budget vetoes

- Related: Michigan has $1B left over from budget. What happens to all that money?

There’s no guarantee the changes will stick, following Whitmer’s unprecedented use of a board comprised of her appointees to dramatically repurpose a budget approved last week by the Republican-controlled Legislature. Former Gov. John Engler pioneered the strategy but didn’t actually use it.

The moves came after weeks of impasse between the first-term Democratic governor and GOP lawmakers, who passed 16 state budget bills without her input.

Whitmer signed the budgets on the last day of the fiscal year Monday night, avoiding a government shutdown and announcing she’d axed nearly $1 billion of the $59.9 billion budget through line item vetoes.

She waited until Tuesday morning to detail the changes.

Whitmer called GOP budgets sent to her on Friday "fatally flawed" arguing they used restricted funds inappropriately and included a "record number of unenforceable and unconstitutional boilerplate language."

"I had to use the powers of my office to clean them up," Whitmer said.

"I do not relish using these powers, but they are absolutely necessary."

In all, Whitmer issued 147 line-item vetoes and declared 72 budget provisions constitutionally unenforceable, while the Administrative Board – comprised of her and her department heads – approved 13 transfers within department budgets.

The funding that was eliminated from the budgets can be renegotiated with the Legislature on how to spend it, opening the door for further discussions on big-ticket spending for things like roads and K-12 schools.

Republican leaders Sen. Mike Shirkey of Clarklake and Rep. Lee Chatfield of Levering weren’t pleased with the changes, which Whitmer has invited them to discuss on Thursday in a closed door “quadrant” meeting.

Chatfield blasted Whitmer on Twitter for rejecting one-time road funding dollars, arguing that “when the governor says she wants more revenue, what she really means is more of your money via taxes!”

Shirkey said Whitmer’s vetoes won’t lead to future policy agreements with his chamber and that he’s “in no rush to participate in Governor Whitmer’s ‘tug of war.’”

Here’s a rundown of what she changed:

Using the Administrative Board

Big shifts in Department of Health and Human Services

- Added $6.1 million for publicity about new rules requiring Medicaid recipients to prove they are working or looking for a job come Jan. 1. Republicans had eliminated funding for the rollout altogether last week

- $9 million was redirected to support the implementation of the new Medicaid work rules requirements from the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity, including eliminating an earmark for the Van Andel Institute in Grand Rapids. Whitmer has criticized GOP lawmakers for not funding their own requirement.

Attorney General

Moved $90.9 million from 43 line items to the Attorney General’s Office to shore up operating funds. Nessel said during the board meeting that the budget passed by the Legislature was “an administrative nightmare.”

School funding

Moved $314.8 million from reserve funds to the department’s operating budget. “This move is critical if the department is going to carry out its mission of educating our children,” said Budget Director Chris Kolb.

Network security

- Moved $20 million to upgrade IT systems within the Department of Technology, Management and Budget

- Moved $2.1 million to speed up forensic analysis of evidence and $2 million to enhance in-car cameras in the Michigan State Police budget.

Environment, health and transportation

- Moved $7.5 million from private well testing and gave it to lead and copper rule implementation in the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy. She also added $1.5 million for home testing.

- Moved $4 million in general fund dollars from a farm grant program and gave it to five programs, including $1.5 million to replace restricted funds and pay for the Pesticide and Plant Pest Management program. Other funds go to emergency management, animal disease prevention, a forest program and a program for minimizing pollution in agriculture.

- Moved $18.1 million general fund dollars to the department that certifies and regulates health care providers and community programs to support community mental health.

- Moved nearly $300,000 out of wildlife management within the Department of Natural Resources, including wildlife, fisheries and deer habitat research.

- Moved around $66.6 million within the Department of Transportation, including $13 million for urban transit to unlock federal fund matching and nearly $40 million to a passenger rail fund.

Using line-item vetoes

Whitmer issued 147 line-item vetoes Monday night, including cutting $375 million in one-time funding for road repairs and $128 million in what she called “pork barrel spending” in the budget that goes to K-12 schools.

This money goes back into an unspent fund that can be renegotiated with the Legislature on how to spend it.

The Legislature can override these vetoes, but it would require a two-thirds majority in each chamber — meaning state Republicans couldn’t do it without the help of their Democratic colleagues.

Among the many items Whitmer nixed:

- Funding for a program that reimburses county jails for housing felons that would otherwise be held in state prisons, and with it a requirement that county jails lose that reimbursement for housing prisoners if the counties have “sanctuary” policies.

- $15 million in grants for monitoring PFAS at municipal airports.

- Around $234 million in spending within the Department of Health and Human Services, including $16.6 million in funding for rural hospitals, $129.5 million in increases in hospital Medicaid rates, and $10.7 million in pediatric psychiatric care provider rate increases.

- $37.5 million for the Pure Michigan tourism campaign.

- $37.3 million for Going Pro, a campaign to “elevate the perception of professional trades” in Michigan.

- $38 million in tuition grants for the state’s colleges and universities.

- $128 million in mostly earmarks within the School Aid Budget, including $4 million for online math and literacy tools, $9.2 million for diagnostic tests, $7 million for career and technical education and $15 million for summer school literacy grants.

- $375 million in one-time funding for road and bridge repairs, including $243 million restricted for four bridges in Dearborn, Ferrysburg, Harrison Township and Lansing.

Declaring unenforceable

Whitmer is not allowed to veto boilerplate provisions that don’t have money attached to them, but she can declare them “unenforceable” if she contends they’re unconstitutional or conflict with existing law. Her predecessors of both parties (former governors John Engler, Jennifer Granholm and Rick Snyder) have regularly used this power and experts say it’s never been successfully challenged in court.

Here’s a few of the provisions she said were unenforceable:

Balance of power

- Provisions in multiple budgets that prohibit agencies from punishing an employee for communicating with a member of the Legislature or their staff.

- A provision that would reduce a department or agency’s funding by 5 percent if they miss a due date to provide information requested by the Legislature.

- A requirement that the auditor general have access to confidential information within the governor’s administration.

Attorney general

- A requirement that Attorney General Dana Nessel submit a cost estimate and go before the Legislature when planning to file or join a lawsuit against the federal government.

- A requirement that she “not enter into any lawsuit that is contrary to the laws of this state” and a requirement that she “enforce the laws of this state.” Those requirements may have been a response to Nessel’s statement earlier this year that she wouldn’t enforce the state’s existing ban on abortion if Roe v Wade is overturned.

Education

The Legislature’s plan to dole out funding to the state Department of Education in four installments, which Whitmer called “a violation of the separation of powers.” That included sections requiring the Legislature’s approval to spend three-quarters of its budget.

Business and economy

- A provision barring the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy from creating rules that would “have a disproportionate economic impact on small businesses” if it doesn’t offset that impact.

- A requirement that the Department of Technology, Management and Budget propose funding increases for a public-private partnership program if it is found to be insufficient.

- A requirement that all contractors for the Department of Transportation verify their workers are legally authorized to work in the United States.

- A provision that would have undermined new road building labor contracts by prohibiting state awards to contractors who signed agreements mandating that subcontractors pay into a union fringe benefit fund even if they do not use union laborers.

Health and welfare

- Requirements that the state Department of Health and Human Services seek approval with the Legislature before spending certain money, including on IT and submit a spending plan before replacing the child welfare system that was the subject of a scathing review for having issues that could harm children.

- A requirement that judges overseeing foster care cases must request input from foster parents.

- A requirement that residential rehabilitation programs treatment requirements “be based on the least restrictive settings and must not exceed national standards for levels of care.”

- A requirement that the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs produce reports at the request of local governments on the marijuana industry’s effect on the community and, if there’s been a negative effect, work with them to create a plan to improve it.

- A provision prohibiting the Michigan State Police from requiring officers to issue a certain number of vehicle violations and evaluating them based on whether they make those quotas.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!