Enrolling in community college is just half the battle

The good news: Low-income students are enrolling in Michigan colleges at a record rate.

The bad news: Many of them won’t leave with degrees.

While more low-income students are making it to campus, they’re more likely to attend Michigan community colleges, where the graduation rates are among the lowest in the nation.

“These kids hit a stone wall when they get to campus,” said Tom Mortenson, policy analyst for Postsecondary Education Opportunity, an advocacy group based in Iowa.

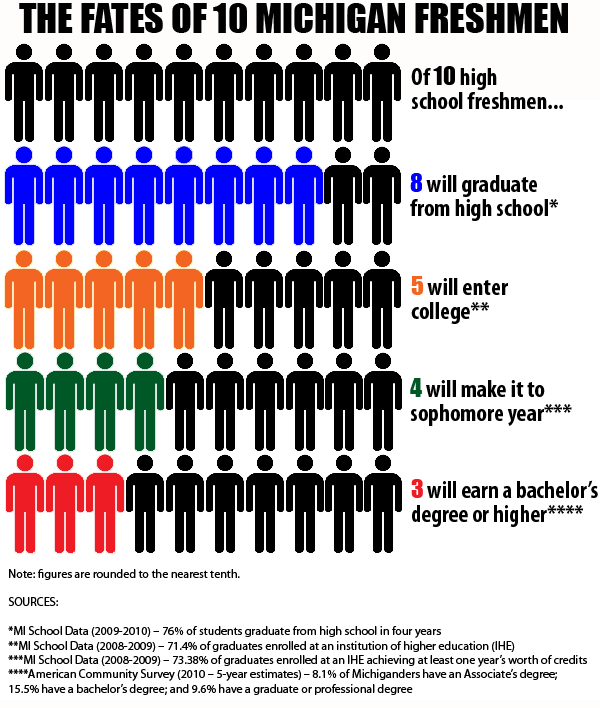

Michigan is falling behind other states in the college readiness race, sending fewer high school grads directly to college, and graduating fewer of them once they reach campus.

The easiest way for Michigan to make up ground is to increase the college graduation rates of low-income and minority students, groups that traditionally have enrolled at lower rates than middle-class whites, said Amber Arellano, executive director of Education Trust Midwest.

An analysis by Mortenson suggests Michigan’s poor are heading to college. Michigan is second in the nation in the share of low-income students enrolled in higher education. About 49 percent of low-income students are enrolled in college, compared to 34 percent nationally.

(Mortenson arrived at the figure by comparing the number of students in fourth through ninth grades eligible for free or reduced lunch, with the number of students at Michigan colleges receiving need-based Pell Grants nine years later. While the calculation may not be exact, Mortenson believes it provides a clear reference for trends and state-to-state comparisons.)

Michigan can thank a bad economy for the trend. “It’s not any policy apparatus,” Mortenson explains. “Kids are geing kicked in the butt by the economy and lack of other opportunities.”

As more low-income students attend college, a greater share are going to community college rather than four-year institutions. In 2010, two-thirds of community college students received Pell Grants, an indicator of low income, compared to 35 percent in 2002. Pell Grant recipients at four-year universities grew at a slower pace in the same eight-year span, from 22 percent to 33 percent.

“Low-income college participation is way up, but they’re overwhelmingly concentrated in community colleges,” Mortenson said. “We’re developing a class stratified system, where if you’re affluent you attend a four-year university and if you’re not, we have a great community college for you.”

It makes financial sense for low-income students to attend community colleges. Tuition is usually less than half of the cost at four-year universities, and kids typically commute to campus from home rather than paying to live in a dorm. Most community college course credits can be transferred to four-year universities if students choose to try for a bachelor’s degree.

But graduation rates are abysmal at Michigan community colleges. Less than one in six community college students earned a two-year associate’s degree within three years.

In 2009, the most recent year for which data available, Michigan ranked 44th among the states in associate degree graduation rates. By comparison, about 55 percent of students in four-year universities earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. In simplest terms, low-income students are going to community colleges where an education is cheaper, but where the odds are longer that they’ll get a degree.

“There’s a lot of emphasis both locally and nationally on non-traditional and first-generation students,” says Mike Hansen, president of the Michigan Community College Association.

To address the graduation rate challenge, Hansen says the state’s community colleges are working to place a greater emphasis on degree completion, rather than just college acceptance:

“There’s a college-going culture of counseling and financial aid, that if you’re the first person in your family to go to college, you may not know how to do that.”

Low income college participation rates by state are simply the number of dependent Pell Grant recipients by state of residence divided by the number of fourth- to ninth-graders nine years earlier who were approved for free or reduced price school lunches in that state.

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!