How much does it cost to educate a child? In Michigan, nobody knows

It is generally agreed that any hope Michigan has of shrugging off its rap as an economic rust-belt straggler depends on creating and keeping bright and shiny new graduates in the state. By the hordes.

But what will it cost the state to produce high school graduates who are ready for college or careers?

Knowing how much taxpayers spend on Michigan’s public schools is not the same as knowing how much it should cost for a good, publicly-funded education, studies show.

For all the debate over whether the state spends enough or too much on education, Michigan has yet to examine the actual costs for a K-12 education that will allow students to compete with students in leading states and around the world.

Michigan taxpayers and legislators simply do not know how much it costs to educate a child. Michigan is one of only about a dozen states that have not conducted what is called an education adequacy study.

“(In Michigan) you know how much a road costs per lane. If you have ‘X’ number of dollars to spend, then you should get ‘Y’ miles of road,’” said Michael Griffith, senior school finance analyst at the Education Commission of the States, a nonpartisan organization funded by the states which tracks legislation and policy changes nationwide.

“We don’t know that with education as much because each state has their own standard. You can’t take a study done in Ohio and know how much it costs to educate kids in Michigan.”

A growing chorus of Michiganders are calling for a study to quantify what it costs to provide all students a good education. Will it mean more year-round schools? Smaller class sizes for elementary grades? Tougher teacher training? More interventions for poor and low-achieving students, or rural students?

Democratic legislators, who are in the minority, are pushing a bill that focuses on determining a price tag to get Michigan students to become proficient in all high school subject areas.

The Dems say they aren’t asking for more money for schools. That wouldn’t stand a chance, said Rep. Ellen Lipton, D-Huntington Woods, co-sponsor of House Bill 5269.

“We want to find out: What are the best practices in successful schools; factors that make for an excellent school. And then say, ‘This is what we want from our schools and this is what it costs,’” she said. “For all I know it could say we’re spending too much. I suspect not, but we have no idea.”

Similarly, the state Board of Education is holding public hearings to hear testimony on ideas for long-term, dramatic changes to how Michigan’s public schools are funded. The board wants to raise money for an independent adequacy study, one that would seek to find out how Michigan can spend money differently– and what amount – to get better results.

“I don't support an adequacy study as traditionally defined. … It’s a term the teachers unions and Democrats use to argue for more money,” said John Austin, the state board president. “We’ve got to better spend money we already spend to get better outcomes.”

Austin contends the state needs to consider weighting per-pupil funding based on the child’s needs. That would mean adding a percentage to per-pupil funding for every child who needs special education, is in a low-income district or needs bilingual education, for example.

“Are we meaningfully making a difference for those who are the furthest behind? That absolutely needs to be the focus of any changes we make in the system,” Austin said.

The School Equity Caucus, a group of about 200 school districts across Michigan from low-income to high-income areas, is split on how to fairly fund schools next year because the districts in the group have differing costs and revenues. But the group supports an adequacy study to figure out the state’s best long-term plan.

“School districts are unique. They have different needs. In some districts they might need one amount per pupil, and another district might need another amount,” said Gerald Peregord, executive director for the caucus.

“Not doing an adequacy study, that’s like not taking your car to the repair place because you might find out you have to put money into it.”

Criticism of studies

Gary Naeyaert, executive director for the Great Lakes Education Project, a charter and school choice advocacy group that wants equal funding for all districts, called the education adequacy movement a “big lie” and money grab.

“What do they mean by adequacy? How do you figure it out what it will cost,” Naeyaert said. “When people start talking about ‘adequate funding’ or what it should cost to educate a child, grab your wallet.”

Adequacy studies conducted in other states do often conclude more funds need to be invested in public education, and the studies themselves cost money and are sometimes used as the basis for lawsuits demanding more adequate funding, said Griffith, the financial analyst at Education Commission of the States.

Lawsuits challenging school funding have been brought in at least 45 states, with most of the recent suits focusing on funding levels for struggling student populations, including rural, disabled and low-income students, according to The Education Adequacy Project, a clinic at Yale Law School.

One influential Republican who might have been expected to support an adequacy study is Rep. Bill Rogers, chair of the House Appropriations subcommittee on school aid.

When Rogers was elected in 2008, he asked the question at the heart of the state’s school funding debate: How much does it cost to educate a child in Michigan? He said he is still waiting for an answer.

But Rogers said that doesn’t mean he believes the state should approve the adequacy study bill and pony up money to pay for data collection.

“Why do I want to pay for a study from outsiders when the information could be there right at the ready at the schools?” Rogers asked.

What’s at stake

The myth-busting study, “A Nation at Risk,” predicted in 1983 a “rising tide of mediocrity” in education in America. Michigan is by all accounts riding that tide – scoring among the lowest achieving states on national tests – at a time when the state’s economy and unemployment rate are clawing up from the bottom.

Michigan is not alone in receiving criticism for perceived inequities in school funding. In “For Each and Every Child: A report to the Secretary,” the Equity and Excellence Commission, chartered by Congress, concluded that education funding nationwide showed “appalling inequities.”

“America has become an outlier nation in the way we fund, govern and administer K-12 schools, and also in terms of performance,” the report concluded. “No other developed nation has inequities nearly as deep or systemic; no other developed nation has, despite some efforts to the contrary, so thoroughly stacked the odds against so many of its children. Sadly, what feels so very un-American turns out to be distinctly American.”

But before Michigan can have a conversation about how to fund schools, it should first determine how much money is needed boost achievement in the state, said Craig Thiel, a senior research associate with the Citizens Research Council of Michigan, a Lansing-based nonprofit research group.

“Is the pot large enough? Michigan has never attempted to find out what it costs to educate a general education student,” he said.

What other states are doing

Michigan is one of about a dozen states that have never conducted an “adequacy study” to determine the costs of providing adequate education, according to a 2010 report from the Center for Evaluation and Education Policy at the University of Indiana.

Critics of Michigan’s current system say the state simply takes the money available for education and asks school districts to budget accordingly. What is needed, they say, is a study that determines the components of a quality education and then prices out how much that will cost.

Outside Michigan, more states are enlisting research-driven studies to determine that cost, according to the Denver-based Education Commission of the States. Typically, the studies recommend that states increase investment in schools.

Some states – Pennsylvania and Maryland, for example – have conducted multiple studies and restructured the way they fund schools as a result, said Griffith, the analyst.

But as some states have found, an adequacy study can be a starting point for budget discussions, but no guarantee for action. “They tell you what you need to spend and won’t tell you where to get the money, because getting the money is a local/state decision,” Griffith said.

“A third of the time, it really does change the system, a third of the time it’s sort of questionable and a third of the time, it’s thrown into a drawer and nobody ever talks about it again because it was poorly done or produced a cost that was astronomical,” Griffith said.

Studies conducted by teachers unions tend to be political grenades, dismissed by opponents, he said.

Keith Johnson, president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers, said he would support the state approving a study conducted by a third party. He is doubtful the legislature will approve it because it would likely say schools need more money and put the onus on lawmakers to do something about it in a state where voters don’t want to pay more taxes, he said.

“This may be self-serving, but a study would show that the unions are not the problem. As long as they don’t do the study, they can keep blaming the unions for everything,” Johnson said.

The state board of education, frustrated that rising education costs have not produced better results, is seeking funding from foundations to conduct a study in Michigan.

“We have new standards, new assessments, new [teacher] tenure reform not necessarily backed by resources,” said Austin, the board president. “It’s important we... use a process to inform us all and end up with some recommendations for change.”

Austin said Michigan needs to know how much it would cost to invest in key practices that improve achievement – better teacher training, for example. An independent adequacy study could also recommend how to better invest in helping poor and low-achieving students, he said.

“There are some very different formulas that deal with what it costs to educate particular children. That is what we need to better understand and probably do.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

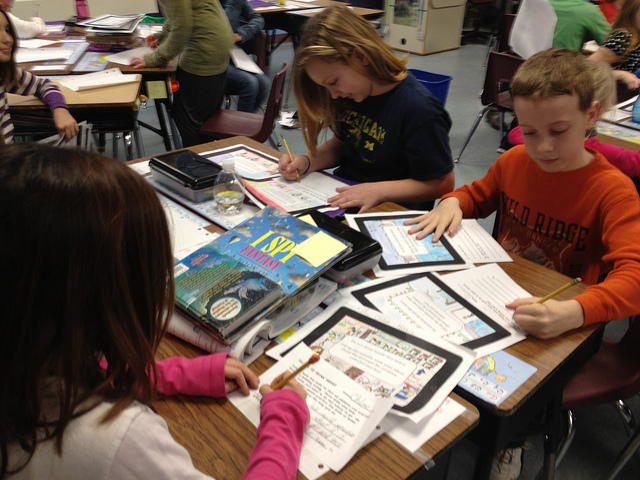

Should the state agree to a study that would put a price tag on a quality education? Perhaps not surprisingly, stakeholders disagree. (Photo by Flickr user Brad Wilson; used under Creative Commons license)

Should the state agree to a study that would put a price tag on a quality education? Perhaps not surprisingly, stakeholders disagree. (Photo by Flickr user Brad Wilson; used under Creative Commons license)