Still last among big cities, Detroit gains big in math on national test

Detroit improves but still last

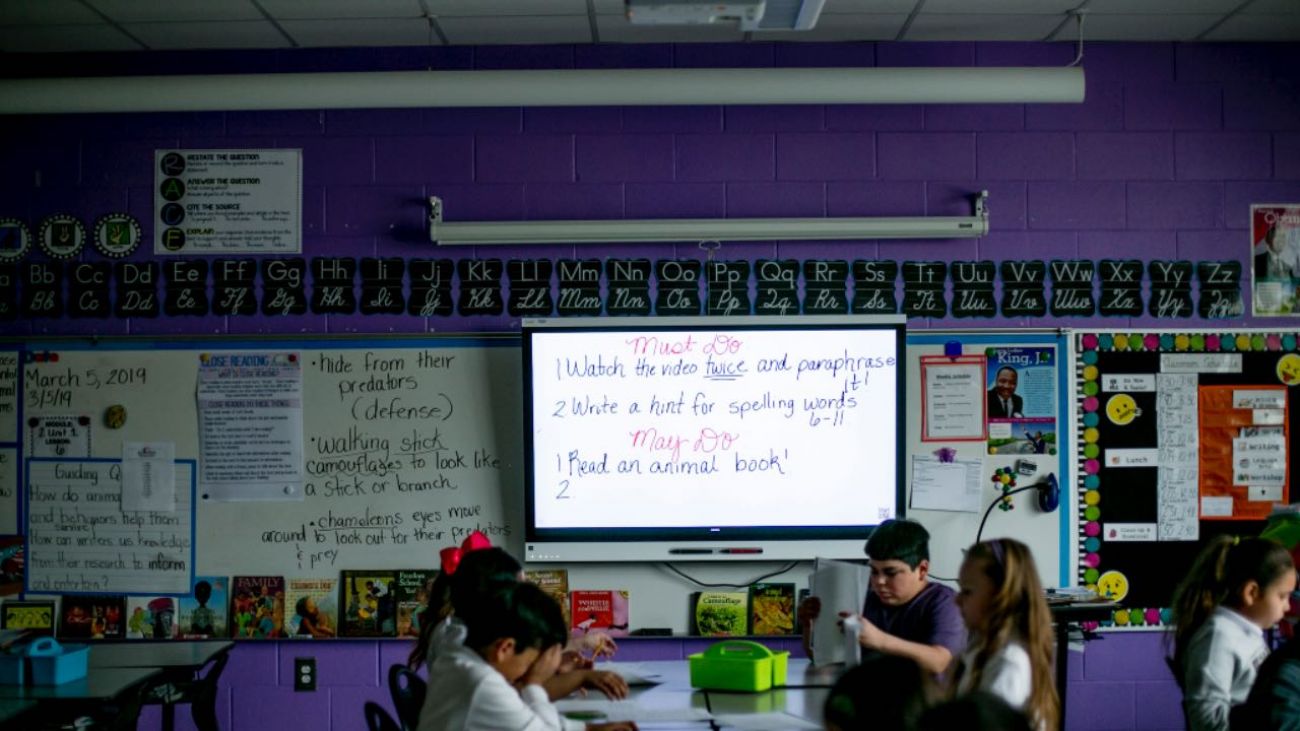

Public school students registered gains in their 4th grade math scores but those remain the lowest of the 27 large urban districts tested on the NAEP. Detroit also has one of the highest poverty rates of those urban distrits.

The nation’s education report card finally contains a sliver of good news for Detroit.

Fourth-graders in the city district scored significantly higher this year on the math section of a rigorous national progress exam than they did in 2017, the last time the test was administered.

But the city’s schools still have a long way to go: Compared to other major urban school systems, the district once again ranks dead last.

“It’s great to see that there was an uptick,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of EdTrust Midwest, an education research and advocacy group in MIchigan. “That’s cause for what I would call a sober celebration.”

Education leaders took the results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress as a sign that improved teacher pay and new curriculums are beginning to pay off for the district, which is still recovering from a near-bankruptcy and a state takeover.

“With only one year of implementation, our fourth-graders quickly showed that they were ready and able to tackle at-grade-level curriculum,” said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, hired to run the district in 2017, adding “Our work here is just beginning.”

- Related: Michigan schools are now average. That’s progress.

- Related: Slideshow: How Michigan schools boosted national ranking

The scores alone don’t prove that Vitti’s reforms caused fourth-grade math scores to improve. NAEP results can be affected by economic trends, changing demographics, and other forces unrelated to education.

Still, Vitti pointed to the district’s promising performance on the most recent Michigan exam ‒ known as the M-STEP ‒as further evidence that a city turnaround is underway.

The district’s performance on the 2019 NAEP stayed flat or improved in virtually every category. Fourth-grade math scores improved by 6 points, a change researchers said was statistically significant. Fourth-grade reading scores saw no significant change. But, in another bright spot, reading scores for fourth-grade English learners increased by 14 points.

“It’s not easy to move NAEP scores by 6 points in two years,” said Peggy Carr, associate director of NAEP. “Take a look at what they’re doing in math and see if there’s any way to extrapolate what’s going on [to other subjects and grades].”

Reading and math scores for eighth-graders remained flat, even as reading scores fell in 13 other cities. But there’s no question that the test scores are a good sign for the district. The last time the test was administered, the math scores dropped significantly.

“These are the greatest gains that Detroit has seen since it started taking the assessment,” said Michael Casserly, executive director of the Council for Great City Schools, in a statement released by the district.

“In addition, Detroit held its own at the eighth-grade level while the nation was going down. Detroit’s gains show real promise for the city school district and its kids.”

The NAEP, which is funded by the federal government, is considered one of the most rigorous exams in the United States. Unlike most state exams, there are no consequences attached to the results, meaning there is no incentive for schools to teach to the test.

The tests were administered between January and March of this calendar year. They were entirely digital for the first time, so the scores were reported about six months quicker than usual.

Since 2003, NAEP has compared scores from large school districts where most students are people of color or qualify for federal lunch subsidies.

Detroit has ranked at the bottom of the list every year since it began participating in the city rankings in 2009. That ranking doesn’t include charter or private school students in the city.

Detroit’s low rank is unsurprising given the district’s fraught history: declining enrollment, near-bankruptcy, and years of state control.

Detroit’s child poverty rate — 55 percent — compounds those challenges. Researchers consistently find that poverty correlates with lower test scores. The urban districts that consistently top NAEP’s rankings typically have lower child poverty rates than Detroit.

Still, there is no reason to think that Detroit can’t close the gap that separates it from other large cities with high poverty rates. Places like Duval County, Florida, where Vitti was formerly superintendent, regularly outperform big city averages.

“We are properly acknowledging our improvement but not celebrating it,” Vitti said, “because our children deserve so much more.”

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!