Tiny school districts to Lansing: Stop acting like ‘middle-schoolers’

Do you have a question about the Michigan budget?

Email Capitol reporters Riley Beggin at [email protected] or Jonathan Oosting at [email protected]

and it could be the basis of a future story.

As principal and superintendent of the one-building Whitefish Township Community School in the Upper Peninsula community of Paradise, Tom McKee recognizes middle-school behavior when he sees it.

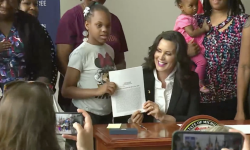

His school district is set to lose 16 percent of its funding because of vetoes by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the failure of the Democratic governor and GOP leaders in the Legislature to come to a compromise in their budget fight.

The 47-student Whitefish Township school system is one of five tiny, rural Michigan school districts on islands or in the U.P. that receive a sizable portion of their budgets from an “isolated district” school fund. That money helps keep the doors open in those districts, and keeps students from having to ride on buses as much as four hours a day to get to the closest adjoining schools.

That funding was vetoed by Whitmer Sept. 30 as part of a negotiating ploy to force Republicans to compromise on the 2019-20 budget.

So far, neither side has budged.

“I call the governor’s office every day,” McKee said. “They tell me ‘We want to fix it but they (the Legislature) won’t negotiate.’ Lee Chatfield (the Republican Speaker of the House) says the same thing about the governor.

“Being in education, it’s like walking into a room of middle-schoolers and they’re all messing around,” McKee said.

Except McKee can’t put the Lansing middle-schoolers in detention.

“I’m disappointed that the 319 kids (the total enrollment in those districts) in the most isolated districts in the state are being used as a political football,” McKee said. “They’re caught up in political games of finger-pointing.”

Whitmer made 147 line-item vetoes in the state budget, cutting almost $1 billion from a budget that was passed by the GOP-controlled House and Senate with no input from the governor. About $128 million of those cuts came in the School Aid budget which funds the state’s public K-12 schools.

Many of those cuts are controversial – $35 million in per-student funding for charter schools, for example – or would seem to fly in the face of priorities Whitmer outlined in her campaign, such as a $16 million cut to career and technical education and $15 million for a summer reading program for third-graders in danger of being held back because of poor reading scores.

The line-item veto of the $7 million isolated school fund is “devastating” to the five districts that rely on the funding to keep their doors open.

Those districts – Whitefish Township in Paradise, Burt Township in Grand Marais, Mackinac Island, Beaver Island and DeTour Area Schools on Drummond Island – all enroll under 100 students. Consolidation with neighboring school districts is problematic because of distance.

Because of low enrollment and low tax bases, the five districts have been the primary recipients of the state’s isolated school funding formula since it was created in 2004. The program has continued through Democratic and Republican governors.

In recent years, the program has been expanded to include funding for about 100 rural districts to help pay for gas to transport children, but other districts rely on the funding for a much smaller portion of their budgets.

If the five original districts don’t receive isolated school funding this year, “it’s going to be catastrophic for all the reasons this was put into place in the first place,” said Daniel Reattoir, superintendent of Eastern Upper Peninsula Intermediate School District, the home of three of the isolated districts.

“Those districts are going to have a hard time fulfilling the Michigan Merit Curriculum” because they will have to shrink their teaching staffs, Reattoir said, referring to a set of state standards and classes that students must meet to graduate. “I know this is political gamesmanship. (But) when it impacts students and the opportunities available to them, it becomes no longer a game.”

About 80 miles west of Paradise, Burt Township School in Grand Marais would lose $221,674 – 23 percent of its annual budget – if the vetoed funds are not restored.

“With that much of a shortfall, we’d need to reconfigure to a K-6 (district) or close our doors,” Burt Township Superintendent Greg Nyen said of the 26- student K-12 district on Lake Superior. “We have enough in our fund balance to continue status quo for the school year. But if this drags out into the new calendar year, then the board is going to be forced to make some difficult choices” about next school year.

The nearest neighboring school district is more than 50 miles away, Nyen said. With winter weather, “our kids would be on the school bus four or more hours a day.”

Young families in Grand Marais are already talking about moving to avoid putting their kids on long bus rides to school, Nyen said.

“That’s going to hamstring our community, because it’s the young people with children in school who do the snow plowing and run our stores,” Nyen said. “If this does turn into a mass exodus, it’s going to have a compounding effect on the community itself.”

Whitefish Township schools would need to eliminate either its elementary or high school grades next year, or close the entire district in June 2021, said superintendent Mckee.

The closest neighboring district is 90 minutes away on a good day. “And on the shore of Lake Superior, we don’t get many good days between November and May.”

Tiffany Brown, spokeswoman for Whitmer said the budget the Republican-led Legislature passed was “fataly flawed,” and the governor wants to negotiate a supplemental budget “to achieve meaningful, long-term funding that will actually support our children and their schools.”

Three of the five school districts suffering major funding cuts are in the 107th House district, represented by Republican House Speaker Lee Chatfield, one of the key people with whom Whitmer hopes to continue budget negotiations.

Gideon D’Assandro, spokesman for Chatfield, R-Levering, told Bridge in an email “these schools should not be targets; they should be priorities. That’s why the Legislature funded these districts.”

Amber McCann, spokeswoman for Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey, R-Clarklake, told Bridge in an email this wouldn’t be happening if the governor hadn’t vetoed the funding.

“The Senate Majority Leader plans to meet with the governor this week regarding her actions,” McCann said.

Burt Township Superintendent Nyen isn’t holding his breath.

“Both sides are using students as pawns,” he said. “It’s not a good situation any way you look at it.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!