Welcome to the New Detroit, white people. So long, poor folks.

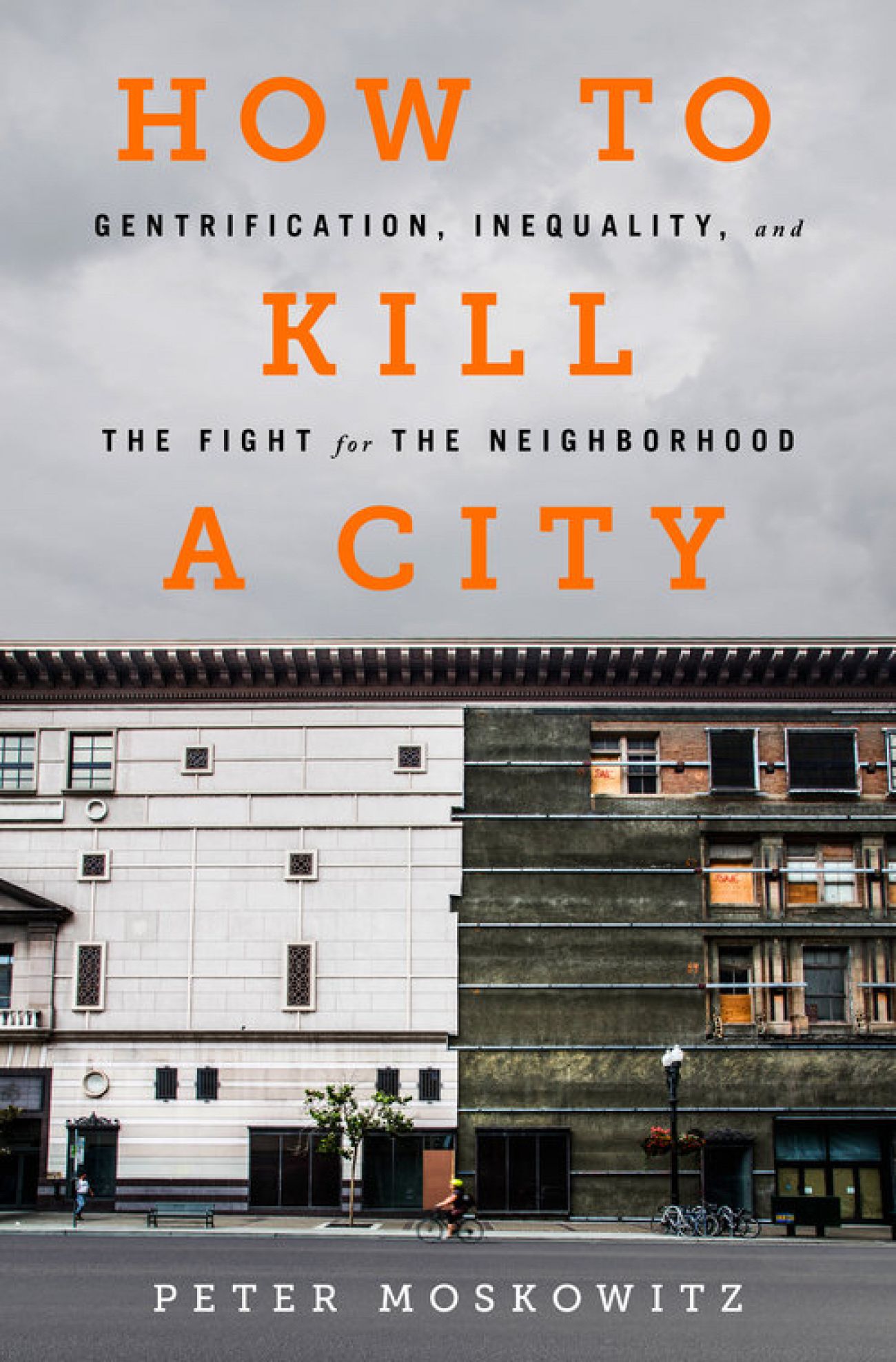

Peter Moskowitz is a journalist and activist raised in New York and based in Philadelphia. His new book, “How to Kill a City,” looks at four American cities that have been transformed by new money in recent years – New York, San Francisco, New Orleans and Detroit.

Moskowitz argues the transformations have displaced longtime residents, especially poorer ones, and replaced them with affluent, mostly white, newcomers who drive up rents and tax assessments and turn what had been vibrant cities into, effectively, gated communities for the wealthy. Detroit is not New York, he acknowledges, but what’s happening is gentrification.

Bridge: The two-city scenario you describe in your book – with the central city doing very well, and the neighborhoods still struggling – is familiar to everyone in Detroit, and not everybody thinks it’s so bad, because at least it represents some recovery, even if it is uneven. Explain why you think it’s bad.

Peter Moskowitz: I don’t think it’s necessarily bad. But the way it’s being done in Detroit, and other cities, increases inequality. What’s happening is not a rebirth of the city but a focused concentration on one particular part of it. Which happens to be one of the whitest parts of the city and the hottest for real-estate development, and that’s where the government is pouring all its resources.

Meanwhile, the rest of the city has kind of been falling off the map. Blocks are still abandoned, until a few years ago there weren’t streetlights, garbage collection was minimal. Take that in combination with the water shutoffs, the tax foreclosures… (and) you get the sense that this is not an accident, that it’s not an organic rebirth, but a purposeful concentration on one part of the city and a purposeful forgetting of the rest of it. It’s a rebirth for a certain set of people, but not for everyone.

There’s evidence the city’s recovery is spreading beyond downtown. Jefferson-Chalmers, the North End and other neighborhoods are showing signs of life after decades of decline. Is it ever possible to see gentrification as plain old improvement? And what’s the difference?

(In the book) I told the story of D’Mongo’s, the downtown bar owned by Larry Mongo. He calls white people the pollinators. For better or worse, the government only shows up, the cops only show up, the street lights only show up, when they “pollinate” a neighborhood. So when you look at this idea of recovery, it’s not a neutral term. Recovery for who? The people who’ve been living in these neighborhoods for decade after decade, keeping their house the only nice one on the block? They’ve been waiting for the government to help them out for a long time.

When you see this quote-unquote revitalization, what you’re seeing is new, mostly white people moving in, and that is followed by government intervention. The people who’ve been there all along are not exactly happy, because they’ve been asking for help for decades and feel they’ve been ignored, in favor of these newcomers.

Every city is unique, but Detroit — and, to a lesser extent, other Michigan cities like Flint — is a city like no other, in that it sprawled to accommodate 2 million people, most from a blue-collar workforce that simply doesn’t exist anymore. How does it compare with other gentrifying cities you looked at, like New York or New Orleans or San Francisco?

Detroit is unique, geographically and city planning-wise. But you can see the same process happening in each.

Gentrification doesn’t have to happen, like, one person on top of another, but it can also be about prioritizing. And I think that’s what you see when you look at the 7.2 (the area of downtown and Midtown) vs. the neighborhoods: Some people’s lifestyles and lives being prioritized — through tax breaks, through incentives, through media coverage — over other people’s lives.

When people talk about gentrification, they tend to compare Detroit to cities like San Francisco and New York, and San Francisco and New York are now essentially gated communities for the very wealthy. But unless there’s some water crisis that turns the Great Lakes region into the Saudi Arabia of water, it’s hard to imagine that happening in Detroit.

People would have said the same of New York in the 1970s, during the Bronx-is-burning era, and now the Bronx is the new hot borough to move to. Rents there are higher than even the hippest parts of Detroit. So this may be a 40-year process, and Detroit is at the start of it. Detroit was built for an era, the supremacy of the automobile, that doesn’t exist anymore.

“Some people’s lifestyles and lives (are) being prioritized — through tax breaks, through incentives, through media coverage – over other people’s lives.”

Do I think that 8 Mile will ever be as gentrified as the 7.2? Probably not, but I think what you will see is kind of a cutting off of the outer city in favor of the gentrified core, which is already happening. So, in 30 years, you might have downtown, Midtown, Jefferson-Chalmers and all of those kinds of places, (and) sort of a virtual fence put around them.

How often do high-poverty neighborhoods like those in Detroit ever make turnarounds, and if so, what works? Do the people who live there have any hope of them getting better without the infusion of better-off white folks?

Unfortunately, usually improvement is synonymous with displacement. That’s just the way the system works.

There’s nothing innate about improvement that can be good for everyone, unless that improvement is coupled with protection. So let’s say there was universal rent control in the parts of Detroit that are rapidly gentrifying. Then, would it be nice that the abandoned buildings were being converted into apartments? Sure. Or let’s say that your home’s value improving wasn’t associated with taxes becoming so unaffordable that most middle-class families can’t afford them? Then, would improvements be nice? Sure, but because of the way our system operates, improvement almost always equals increased pressure on the poor and middle class.

Your proposed solutions are mostly government-based — rent control, higher taxes, more focused spending on the poor. That’s kind of a pipe dream in Michigan right now, and particularly in Detroit. What do you think is possible in a place like this?

On the government level, I’m pretty pessimistic. Even in New York, which has one of the most progressive mayors, Bill de Blasio’s housing person came from Goldman Sachs. There’s no such thing as a development-skeptic mayor at this point, I don’t think. If you look at Detroit, things like the community benefits ordinance, which passed, although in a watered-down form, was a sign that people are ready to take these things seriously.

This is not an issue that (Detroit Mayor Mike) Duggan is going to be able to work out at the city level. It’s about state taxes, about the county, and especially about the extremely low taxes we have on the wealthy at the federal level. You can’t run a city full of poor people with no tax revenue. So what can Duggan do about that? Limited amounts within the city, but there are all these mayors getting together to talk about $15 minimum wage, etc.

But the larger problem is, we don’t think of housing politically in this country at all, ever. During the presidential debate, it was mentioned not once. Housing is usually our No. 1 expense. We have all these food justice movements, poverty, racism, and housing is part of all of that. And yet, we don’t really talk about it. The first steps to a more equitable city is that grassroots refocusing and rethinking.

Any final observation about Detroit you’d like to make?

You could use more public transportation.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!